Does Anyone Know What To Do About Jobs?

Screenwriter William Goldman (“Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”, etc.) is often quoted for saying about Hollywood, “No one knows anything”. The comment was wasted on Hollywood. He should have said it about government and its notions of how to cure unemployment.

The desultory jobs numbers paint a grim picture of the American economy and diminish Barack Obama’s prospects for re-election. Mitt Romney, who has pulled ahead in recent polls, believes his experience at Bain Capital gives him a better understanding of what is needed to restore the nation to prosperity, and voters may turn to him for answers. Barack Obama’s answer to Romney: “If your main argument for how to grow the economy is ‘I knew how to make a lot of money for investors’, then you’re missing what this job is about”.

The fact is, neither has the answer. Presidents have a limited role in creating jobs, and we are foolish to give them credit for the good times and blame them for the bad. The roots of today’s problem lie much deeper. But in-depth analysis is not how we pick our presidents.

The Republican leadership calls every action by the Obama administration “job killing”, especially any proposal to tax “job creators” (both phrases apparently must be inserted into every sentence), and the President tours the country railing at the obstructionist Congress. Nothing goes forward.

The Republican strategy has been to throttle every attempt by Obama to produce jobs, and then to blame him for causing persistent high unemployment. They have successfully portrayed the 2009 stimulus as a failure and for the most part have stifled any job program in the three years since. Obama went before a joint session of Congress last September to propose his American Jobs Act, repeatedly exhorting its members to “pass this bill”, but it would be pronounced “dead” by Republican Majority Leader Eric Cantor just weeks later. Blocking Obama is in keeping with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s crusade that “the single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

It is remarkable how well the strategy of casting blame on the Obama administration seems to be working. All the while, a budget passed by the Republican-controlled House with deep cuts guaranteed to cost jobs in the hundreds of thousands goes unnoticed.

For his part, Obama has always played small ball, scaling back his initiatives so as hopefully to get Republicans to go along. He has tried for singles while his believers have wanted him to swing for the fences. Had he done so, he would at least have been on record for thinking big. Inside the Beltway, defeat at the hands of Congress is thought to make a president look weak. Outside, it is the reverse. For not challenging Congress, however unyielding; for tailoring bills to Republican likes in the hopes of winning their cooperation; for not making the more sweeping proposals for change that his followers had expected, he has made himself look timid.

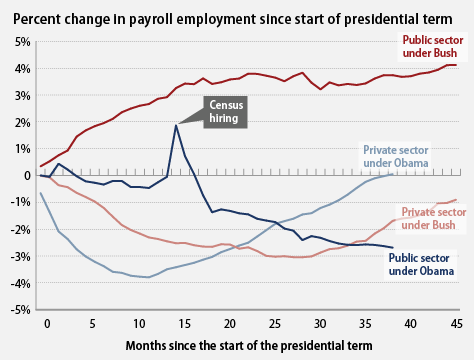

Also weighing somewhat unfairly against Obama is that so much of job loss is the relentless decline in public sector jobs at the state level (chart below).

What would Mitt Romney do? Asked in a Time magazine interview what would lead to “a lot of new jobs”, he evaded with “there’s not just one element that makes the whole economy turn around” and “for someone who spent their life in the economy, they understand how that works” and “[Obama] doesn’t have a clue what to do to get this economy going. I do”. There is a plan, though. It is more tax cuts.

Tax cuts being the be all and end all of job creation for Republicans, Romney would cut corporate taxes from 35% to 25% and individual tax rates 20% across the board. And he wants to make the Bush tax cuts permanent. As it stands, all revenue collected by the federal government totals just 14.8% of our gross domestic product, the lowest in some 50 years and a shortfall that is a huge contributor to the deficit. Romney’s added tax cut would add another $150 billion a year to the problem according to the Tax Policy Center.

But Romney would recover the revenue lost by eliminating deductions. He would eliminate the second home mortgage deduction for high income people, those earning above $250,000 a year. Also the state and local tax deduction, but again only for the top tiers. The former would be a revenue gain of a mere $2 billion — and that’s if the second mortgage deduction were eliminated for everyone, not just the wealthy. The latter would offset his tax cut by only $25 billion. Pressed on the point, he answers only that other deductions “will be something we’ll work out with Congress”.

Obama’s stimulus was a dog’s breakfast of scraps, and a third less than Keynesian economists thought would be effective. Much of it was unemployment benefits and life support to states with money for Medicaid and to keep public service workers (police, fire, teachers) on the job for a time. It was poorly designed to create new jobs. Adding up the detail at the government website, one finds only a minuscule portion — perhaps $60 billion — that can be called true “Contracts, Grants and Loans”, the labeling notwithstanding. Had the stimulus been massively for infrastructure, we would at least have seen some return for our money.

If the stimulus didn’t do much to create jobs, would more tax cuts have been the answer? But 39% of the stimulus — $245 billion of the original $757 billion — was tax cuts. The purpose was to win Republican votes in Congress, but not a single member broke ranks. And in Obama’s follow-up, the “dead” American Jobs Act, which had to be broken into pieces in the hopes of getting something through Congress, the half that made it through was — once again — a tax cut: the continued reduction in the payroll tax. Along with the lesser reduction of last year, that put another $245 billion of tax savings into consumers’ pockets.

So we’ve seen almost half a trillion dollars in special tax cuts across the last three years, which, combined with the prolongation of the Bush tax cuts at about $115 billion a year, have left $850 billion or so in the economy, which, according to Republican theology, should have created a lot of jobs. Yet the job numbers are weak and unemployment just rose a 10th of a percent to 8.2%.

Republicans had to explain away the failure of these tax cuts to produce jobs. They were the wrong sort of tax cuts in the stimulus, we are told, and temporary tax cuts such as the two-year trimming of the payroll tax do not work; only cuts that are “broad-based, immediate and permanent” said Republican House Leader Eric Cantor. The two-year extension of the Bush tax cuts were somehow exempt from this logic.

Poor job creation was also the case during the George W. Bush years. His tax cuts were estimated to have increased the national debt by $1.8

Bush and Obama Job Creation: At this point in either president’s term, public sector jobs

had continually risen under Bush while private sector jobs were

still dropping, whereas

under Obama, it is the continuing decline in public sector jobs that is keeping the

unemployment rate at 8% and above.

trillion in their first 10 years, yet over his eight years in the White House, job growth was only 2% (versus population growth of 7.5%), the most tepid decade of job increases since before World War II. And that does not count against his term the huge plunge in jobs of the first few months of the Obama administration before the actions of a new president could have had any effect.

So it should not be surprising that the public greets proposals for still more tax cuts with cynicism, finding all the talk of “job creators” just a ruse for rewarding wealthy campaign contributors. The Tax Policy Center says that under Romney’s tax plan, those earning more than $1 million a year would get to keep an average of an extra $295,874 every year.