Voting for Romney? Don’t Expect His Tax Plan to Work

Mitt Romney’s plan is to reduce every tax percentage bracket by 20% but promises there would be no reduction of government revenue. To backfill the shortfall he would limit or eliminate some of the deductions and exemptions that would particularly affect wealthier taxpayers and not middle income earners, but he has refused to specify just which such “loopholes” he has in mind. He says those details would be worked out with Congress. The question is, what will we be asked to give up in exchange for another tax cut?

Setting aside for the moment the wisdom of cutting taxes still further when the country is $16 trillion in debt, the principle is sound: first, to streamline a tax code encrusted with years of barnacles that have made taxes impossibly complex (the 1040 instruction booklet has grown to 179-pages, and that’s without forms); second, to “broaden the tax base” by eliminating some of the exemptions, deductions, rules, exceptions, and special interest dispensations, thereby exposing more income to taxation.

Romney would retain all the Bush tax cuts. The 20% further cuts would be applied against that base. He would repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax (a recalculation of taxes originally meant to limit deductions by those with higher incomes); eliminate altogether the tax on long-term capital gains, dividends, and interest income for those with incomes below certain thresholds (e.g., marrieds filing jointly with income under $200,000), but would leave intact the preferential 15% rate on capital gains and dividends for those in higher brackets (75% of those benefits go to the top 1% of taxpayers). And he would repeal the federal estate tax.

That results in quite a hole in the budget. The non-partisan Tax Policy Center (the Romney campaign endorsed its “objective, third-party analysis” in November 2011) looked to 2015 and projected that the tax cuts alone would reduce revenues by $456 billion.

tax expenditures

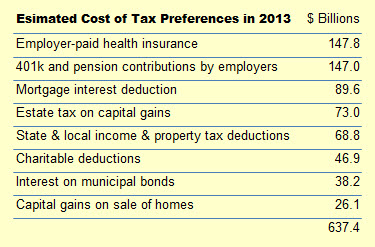

Because Romney has said that he would fill the hole by limiting exemptions and deductions — improperly called “loopholes” and better called “tax expenditures” — on the wealthiest, the Tax Policy Center (TPC) looked at that population group first, with the objective of seeing which and how many of the expenditures needed to be closed to pay for the $360 billion revenue hole that the 20% cut caused in this group.

The answer is that there are not enough to re-fill the hole. The government would get $87,117 less on average from those earning over $1 million a year, because the elimination of $88,444 in deductions, exemptions, etc., would not be enough to offset a $175,961 drop in taxes caused by Romney’s 20% cut.

It is therefore baffling that Gov. Romney can say, as he did in the second debate, “I’m not going to have people at the high end paying less than they’re paying now”.

The TPC continued downward through the successive tax groups and discovered that when they get to families earning below $200,000, the situation is reversed. The deductions they would have to sacrifice toward making the Romney plan ”revenue neutral” would exceed the savings brought about by their 20% rate cut. So they’d pay higher taxes. Those in the $50,000 to $75,000 range, for example, would see their taxes rise by $641. One of the groups — taxpayers with children and income below $200,000 — would see taxes increase by an average of $2,041, which is the source of the Obama camp’s claim that the middle-class would pay $2,000 more in taxes. This happens because some of the most cherished of the deductions and exemptions must be taken away from even the lower income groups in order to cover the $456 billion shortfall of the 20% cuts.

conundrum

As the table shows, there aren’t enough tax reduction categories to close without taking away the mortgage interest deduction, or taxing the value of company-paid health insurance, or taxing company contributions to 401k plans, or ending the deduction of state and local taxes. The Romney plan would have to take away 70% or so of all of them, and for all income groups. Otherwise, the math doesn’t work.

Compare that takeaway to the $87,117 windfall that the million dollar and over group would enjoy (far more for the wealthier such as Romney himself) and add to that Romney’s intention to preserve their (and his) 15% tax rate on dividends and capital gains, and you have a voting public increasingly at odds with his plan the more they learn of it.

But what if he could make his plan revenue neutral by offsetting revenue loss by eliminating “loopholes”. The Republican playbook says that tax cuts create jobs. But that’s not a tax cut. Overall, it leaves everyone with the same taxes. Yet he says that 7 million of the 12 million jobs he promises will come from his tax plan.

But perhaps there’s another way around this dilemma: All tax breaks of every stripe reportedly total $1.1 trillion a year. The table shows only the biggest; almost all others save taxpayers smaller amounts. But doesn’t that leave a vast number of smaller items — in fact, an almost magical $462 billion ($1.1 trillion minus the table’s $637 billion) — that Romney could wipe out to pay for the $456 billion gap?

Yes, but consider the blizzard of special interest exemptions and deductions that lurk behind that $462 billion, every one of which will bring squadrons of lobbyists to the corridors of Congress to plead (and pay for) their preservation. And now imagine the likelihood of representatives and senators turning them all away in deference to a President Romney.

backpedaling

Romney has begun to play defense. At a Denver radio station he contemplated maybe limiting deductions to, say, $17,000 per family as a way to pay for the cuts (which he raised to $25,000 in the second debate). Or he is reportedly considering modifying the standard deduction, a hot button because it would affect most taxpayers. Or taxes on employer-paid health insurance above a cutoff lower than that already contemplated for lavish so-called “Cadillac” plans.

Advisors at the American Enterprise Institute have suggested that Romney could simply reduce the tax cut percentage to whatever extent that Congress proves uncooperative, but the Romney campaign says the candidate is committed to his goal of 20%.

Now Romney officials are saying that “revenue neutral” still works because the tax cuts will generate the economic growth that will bring in higher tax income to fill the hole. But economists argue that tax cuts are one of the weaker ways to raise an economy. After all, the Bush tax cuts were quite steep, yet job growth during his eight years was the weakest since World War II and we wound up with the Great Recession and huge job losses. Yet the Republican answer to stimulate jobs and growth is nevertheless always tax cuts. In an August CNN interview on another subject, Romney said another government stimulus program is not the right course, that the first one did not work and “expecting a different result is, as famously said, the definition of insanity”. So, Governor, how should we characterize trying a tax cut yet again?

The campaign had better hope that growth will offset the revenue loss, because the whole subject of tax cuts versus tax expenditures is really no more than a thought experiment. The prospect of Congress voting to wipe out everyone’s tax breaks is nil.