Should High-Speed Trading Be Curtailed?

We say slow it down and tax excess Oct 12 2012The near death experience of Knight Capital was only the latest in a series of improvised explosive devices that have rocked the markets and caused individual investors, some believe, to run for cover rather than continue investing in stocks. Inadequately tested software ran wild for a full 45 minutes at Knight, causing a $400 million loss for a firm that accounted for fully 11% of all trading in the first half of the year.

In March a software glitch at BATS Global Markets, the nation’s third largest exchange, buffeted the markets by disrupting trading for a sector of the alphabet that included BATS itself, blocking trading in the firm’s own stock on the day it went public.

And then there was high-frequency trader Infinium Capital Management in February 2010. Much like at Knight, software algorithms were put online a day after they were written after testing of only a couple of hours. In three seconds 6,767 orders to buy light sweet crude oil futures were pumped into the New York Mercantile Exchange, roiling the futures market.

These are recent examples of the dangers of rapid-fire trading driven by complex software algorithms that can never be guaranteed as bug-free. In all three cases it is a fairly safe bet that management — in its infinite ignorance of software — ordered that systems be rushed into production rather than lose time and money testing, leading to colossal loses of money. That mentality hasn’t changed, which means it will happen again.

the good part

Electronic trading has brought down the cost of buying and selling securities to a level unimaginable a few decades ago, when a typical trade cost hundreds of dollars in brokerage commissions and was handled manually on the floor of an exchange. In just the last decade the average cost of trading a share has been cut in half and is now reckoned to be 3.5 cents, says Abel/Noser, an outfit that analyzes trading costs for clients. Speed has also brought hugely increased liquidity — the ability to immediately find a buyer or seller. And multiple electronic exchanges, as well as the conversion to cents where prices were once no more granular than eighths of a dollar, have squeezed the bid-ask spread (the price difference between what someone will pay and at what someone will sell) to the vanishing point.

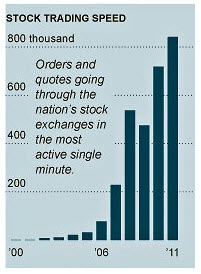

But high-speed trading has taken over the markets, accounting for 55% of all trading — 65% of equities (stocks). Trading volume has zoomed. In the 1970s, a 20 million share day could break the back offices of Wall Street firms; today, trading ranges from 8 to 15 billion shares.

High-speed trading involves finding tiny price disparities in the feeds coming from exchanges and buying at one in order instantly to sell at the other, with stocks held for only moments. Harmless, it may seem. But there are growing concerns that high-speed trading is manipulating the markets. Trading speed once measured in thousandths of a second (a blink of the eye takes 300-400) is now moving to millionths of a second, which has enabled firms to flood exchanges with buy or sell orders, only to cancel them an instant later as a way to discover market prices. Excessive orders could be used to deliberately overload systems to slow trading by others when that may confer an advantage. The truth is that what is going on that hidden world is simply unknown.

The bigger rapid-fire trading firms are even placing their servers on the premises of the electronic exchanges, plugging into their direct price feeds before others get them, and using their physical proximity to move trades across the wire before more distant competitors. Even the speed of light takes time in that world.

None of this has to do with the fundamental value of companies; none of it has to do with investing in those companies. The speed and liquidity of today’s trading platforms are a vast improvement over the now quaint world of ticker-tapes and floor specialists. But high-speed trading is another matter — what has been called a “Frankenstein” market taken over by computers trading with each other at incomprehensible speeds, exploiting tiny price differences solely to make money, none of it offering any public good.

Robin Hood meets Frankenstein

That has periodically given rise to a demand that all trading be charged a tax, a “Robin Hood” tax to keep Frankenstein at bay, That was the name given to a short-lived populist movement last year, inspired by anger at banks, that argued for charging fees for trading and for giving the money to the world’s poor. Billionaire philanthropists such as Bill Gates and George Soros spoke up for the idea, joined by Vice President Al Gore, consumer activist and perennial candidate Ralph Nader, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Pope.

Government figures were quick to join up: governments need money. French President Sarkozy was for it. Two Democratic senators proposed charging $3 in taxes for every $10,000 of transactions in the U.S. They said it would yield $350 billion over ten years.

But British Prime Minister David Cameron thought it an abominable idea: unless it were imposed worldwide, the tax would drive trading business away from England’s shores. President Obama, hopeful of raising election money from Wall Street, said much the same.

But why tax all trading? What sense is there in penalizing individuals for investing — otherwise known as saving — which we are all encouraged to do?

Instead, why not engineer a fee for only high-volume trading — a tax that would only kick in when in any given day, or hour, or minute a firm’s trades — those bogus trades and their cancellations we mentioned, as well as genuine buys and sells — exceed a certain number? A tiny charge per trade applied when that volume tripwire is hit, but enough to add up to serious money when a firm allows the number of trades go through the roof as has become standard practice today.

The accompanying chart makes the point.

Financial Information Forum

Rising from almost nothing just a few years ago, 2011 saw a day when over 800,000 trades went through in a single minute. What for?

A tax on manic trading would certainly slow trading. Algorithms would be altered to cause them to think twice about cost effectiveness before barraging the market with trades for overly tiny price differences.

There is no rationale for taxing such trading — unless faulty software continues to crash the market, or perhaps to retaliate against ever-expanding server farms that cook the atmosphere with their demand for power. But if the middle class is to be protected from tax increases, other ways are needed for the government to increase revenue. At around 15% of gross domestic product, federal revenue is the lowest in half a century.

We tax everything else — gasoline, telephones, alcohol, cigarettes — these are just a few in a long list. Taxing sugared soft drinks was considered as one way to pay for Obamacare (until the soda lobby bought off Congress). So a tax to thin out the obesity of bloated trading volume is equally justifiable as a modest means to chip away at the nation’s deficit.

Please subscribe if you haven't, or post a comment below about this article, or

click here to go to our front page.