How to Increase Prospects for Low-Income Kids

And catch up with the rest of the world in the bargain Jan 30 2014The commentariat is already calling the president a lame duck, as if deciding we should just drift for the remaining 1,000 days left in his second term. But when Barack Obama stepped to the podium for his fifth State of the Union address, he  showed firm intent to get things done and, as expected, expressed his desire for fixing two key failings of America’s approach to education that sap the nation’s strength: lack of early education of pre-kindergarten (pre-K) kids and the poor job colleges do in finding gifted kids among the lower rungs of our society.

showed firm intent to get things done and, as expected, expressed his desire for fixing two key failings of America’s approach to education that sap the nation’s strength: lack of early education of pre-kindergarten (pre-K) kids and the poor job colleges do in finding gifted kids among the lower rungs of our society.

"Research shows that one of the best investments we can make in a child's life is high-quality early education", he said, asking Congress to "get this done". What gave the pre-K movement a boost was the release last fall of the international PISA scores. Every three years the Program for International Assessment tests 15-year-olds around the world in reading, math and science. The U.S. results were dismaying: 26th in math, 17th in reading, 21st in science.

Kids from affluent families score higher. The problem is with children of low income households who suffer from low exposure to language and learning from the moment they are ready to talk. Poorly educated parents pass along their own shortcomings. Early education — schooling for a couple of years before kindergarten — has become a hot topic as a hopeful remedy.

Recent research at Stanford found that, because parents in more affluent families talk to their children so much more, their children at 18 months identify simple words faster than toddlers from poor households. By six months later, they had learned 30% more words. By age 3, kids from better educated parents hear 30 million more words than their counterparts at low-income households.

The claim is that a lack of early learning and exposure to reading produce a continuing setback to a child’s ability to learn in school thereafter which is typically never overcome throughout the education years, and that leads to poorer jobs or possibly unemployment. Society pays the price: higher social welfare costs, heightened crime rates, and lower tax revenue.

Those are big claims and critics point to a study by the Department of Health and Human Services that looks at nearly 50 years of Head Start, the program that attempts to broaden experience for disadvantaged kids. It concluded that “pre-school has no lasting impact on children’s future educational success”. The gains “disappeared by the third grade”.

Other studies say maybe so, but inner-city kids from low-income homes who attend pre-school exhibit skills such as self-control, planning, and cooperation, go further in school and are less likely to become pregnant as teens, and less likely and slip into crime.

If this seems like some squishy liberal concept, talk to the military, which is concerned for filling the ranks with sufficiently educated troops. Two former Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs, Generals Henry Shelton and John Shalikashvili wrote,

“it’s clear to us that our military readiness could be put in jeopardy given the fact that nearly 75% of young Americans are unable to serve in uniform… we believe that investing in our children through early education is not a Republican issue or Democratic issue. It’s a plain common sense issue critical to our National Security”.

There are a couple of long-term studies, one from Ypsilanti, Michigan, that began in the '60s and another a decade later at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where test groups of low-income kids were given free pre-school and were followed thereafter. Differences in how their lives turned out compared to others’ in their social groups were marked: they were more likely to have graduated from high school, to be employed, to own their homes; less likely to need social services, or to have been arrested.

Such attention to tiny kids age 3 and 4 doesn't come cheap, but the consequences of neglect are more costly by a wide margin. So says James Heckman, a Nobel economist from the University of Chicago and fervid advocate of pre-K who lectures around the country. In 2006 he and associates did a cost benefit analysis of those in the Ypsilanti study vs. their peers — how much did society benefit, for example, in taxes on higher earnings; how much did society save in reduced costs such as safety net welfare and, for some, incarceration. Heckman calculated that the program cost $17,759 per child per year in 2006 dollars (the date of his study) but “each dollar spent at age 4 is worth between $60 and $300 by age 65”.

It is the states that are embracing early education the most. Fifteen governors, more of them Republican than Democrat, have instituted pre-K programs, with spending on early education running $400 million higher than before the 2008 economic collapse. Oklahoma is acknowledged to lead the pack with a rigorous program. Sessions have only 10 children per teacher and teachers required to have college degrees and training in early-childhood education. Oklahoma’s position is that “skimping on quality to save money could undermine the entire effort.”

Meanwhile, the federal government ruminates. The President has already urged national pre-K in last year’s state of the union, and Congress…well, we all know about Congress. House Speaker John Boehner is on record saying that the federal government getting involved in early childhood education is a “good way to screw it up”.

Pre-U

At the other end of the education spectrum are those bright teens in the pre-University years who come from low-income homes and have no idea that they could get a first-rate college education, especially at some of the best schools in the country — and fully paid for. In what can only be called a waste of human capital, only 44% of high school seniors from low-income families who score high on SAT tests enroll in a four-year college, according to a Century Foundation report. They tend to stay close to home and go to local community colleges, if at all.

Beginning in 2008, Ivy schools began blanket policies of sliding scale tuition discounts to families with incomes below a certain threshold. Harvard led off, charging 10% or less of a family’s income to households with $180,000 or less in income per year, for example. Others followed. At Yale, the bottom of the sliding scale is that families who earn less than $60,000 a year pay nothing. The premier private universities, with their loyal and successful alumni, have built up enormous endowment funds to pay for this largesse. Harvard sits atop a fund worth $30 billion.

But youths and their parents in the lower socio-economic strata have been proven in the few years since to be largely unaware of such offerings. The benefits have gone predominately to middle class families.

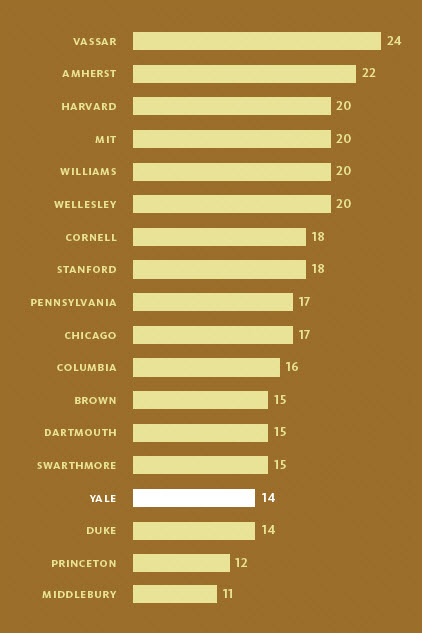

Chart shows percentage of students at each school who received Pell grants, the commonly used indicator that a student is likely from a lower income background.

A chart in Yale’s alumni magazine was honest enough to fess up to that school’s poor showing alongside other highly selective schools, but it has company. An article titled “Wanted: smart students from poor families” admits that 69% of the class of 2017 come from families that earn over $120,000 yearly. That squares with a Georgetown University study of the country’s 193 most selective colleges. Only 15% of students entering the 2010 freshman class were from the bottom half of the income spectrum, while 67% came from the top quarter.

In fairness, private colleges without government support must admit a certain number of “legacy” students — kids whose parents went to the school — in order to attract the contributions that make their subsidy programs possible. But the Yale article comments that economically the student body “looks like America turned upside down”.

Public colleges across the land also have subsidy programs. But to keep them alive they have had to ask wealthy and middle-income families of students to pay higher tuition because of straitened state budgets and legislators who are pulling the oars in the opposite direction. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports that all but two states spend less per student — a quarter less nationally — than before the 2008 downturn.

Obama convened over 100 college presidents from all over the country in mid-January — a summit to which only those who had pledged action to help low-income students gain access to their colleges were invited. It is Obama’s intent to do what he can, absent a willing Congress, to improve chances of upward mobility for the lowest rungs of the society in a country where the rate of mobility has not declined, says a new report by Harvard’s Raj Chetty, but has long been stagnant and is now lower than that of other countries.

Colleges have largely taken a field of dreams approach; they offered the opportunity but the students did not come. The problem is a lack of awareness. Kids and their parents in pockets of Appalachia or Louisiana bayou country or small towns in Montana assume that the top schools are closed to them. The answer lies in sending information packets to high school teachers around the country — “We are looking for a few good students” — and in enlisting alumni living across the map to canvass schools in their area.

But once those bright and overlooked candidates from the bottom economic tiers are found, admissions offices will need to change their practices if the kids are to get a fair shake. Wealthier applicants effectively get preferential consideration, however unintentional, says Anthony Marx, who pioneered outreach to low-income students while revolutionizing Amherst’s admission policy when its president. He points out that well-off parents can afford SAT coaching, and to pay for taking the test more than once, and to pay for overseas travel, and their children are free to devote idle time to community service projects — all enriching their résumés and earning more points with admissions administrators. The playing field is not even. “Colleges don’t recognize, in the same way, if you work at the neighborhood 7-Eleven to support your family”, says Marx, and those are the kids that the top schools should be looking at. That aforementioned Yale alumni magazine article? It was written by a recent Yale grad who had gone to prep school and was taken with the fact that his assigned roommate at college was an Idaho pig farmer.

Please subscribe if you haven't, or post a comment below about this article, or

click here to go to our front page.

The Chapel Hill, NC, is about all the evidence that supports pre-K education, which isn’t to say I’m personally against it, just that the facts are not that conclusive or overwhelming.

But, let’s look elsewhere and at other things. One of the most successful charter school programs is in Newark, NJ, with one of the worst-faring urban minority populations in the country. It appears overlooked by the rest of the country. It has been a bi-partisan effort, though the teacher’s unions don’t like it–b/c it takes $ out of the schools. The charter schools educate students at 90% of the cost of public Newark schools. About 20% of the kids in Newark are in chartered schools now. Last year one school had a class in which every child either left to a four year or two year college.

So, what do they do differently? Each one is a little different, but they all offer a longer school day and a lot of focus on discipline. There is a lot of reprogramming of some kids so that they will be prepared for broader society. The parents in this population not only lack education very often, but the family structure often isn’t strong and discipline is loose.

One of the questions that has been asked is how will these kids do after they are outside the structure provided in school. We’ll learn soon. But, at least what’s happening here covers a lot of students from very challenging backgrounds and provides many avenues to tackle these issues.

People should watch closer.