Supreme Court About to Decide Fate of Obamacare

Should the government be barred from paying subsidies to persons buying health insurance because seven words in the 602-page Affordable Care Act fail to Court OKs Subsidies: June 25: In exactly the 6-3 split that the adjacent article forecast, the Supreme Court has validated the federal government’s paying subsidies to those who sign up on the federal exchanges. The justices’ logic matches what we set forth here.

So argue the briefs before the Supreme Court in King v. Burwell, the long-awaited case that could cripple Obamacare. The Supreme Court is expected to render its verdict as soon as this Friday. THE FINE PRINT

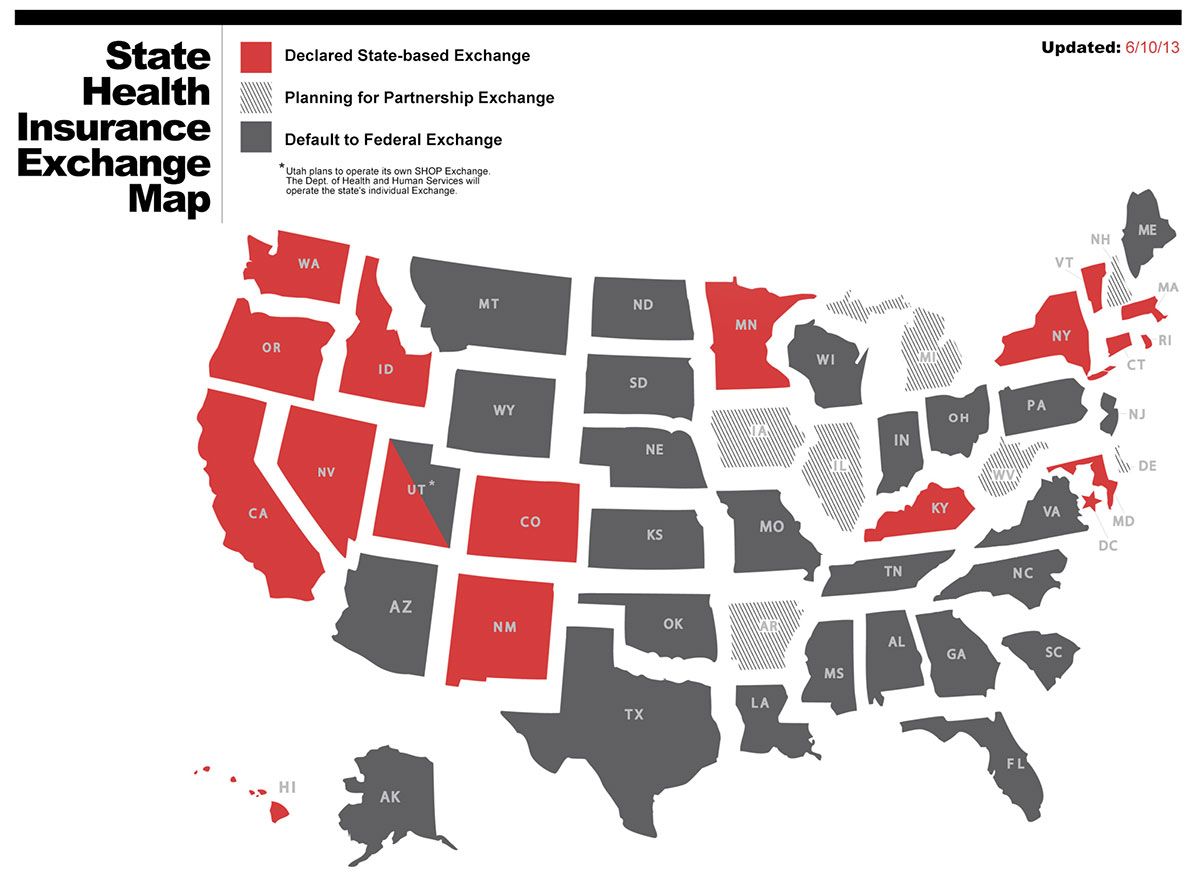

For the 34 states unwilling to mount their own exchange, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides for the federal government to establish and manage an exchange in their behalf. The text then says that subsidies are to be granted to low-income people who sign up for insurance “through an Exchange established by the State”. Missing is any explicit wording that says the federal government is also authorized to pay subsidies to persons who sign up on the exchanges it runs.

A drafting error, say those who insist the mission is the same no matter who administers the exchanges. The obvious intent is for all Americans to be treated equally.

A decision that prohibits the federal government from issuing subsidies to those who signed up on the exchanges it runs would sink Obamacare, which is precisely the objective of the group that searched the Act for an Achilles heel, found those seven words, and sued the government. If denied those subsidies, an estimated eight million could no longer afford the insurance, with only the sickest paying no matter the cost, meaning the insurers will need to spiral premium costs upward to pay for the care of these most expensive policy holders, and that will drive still more people into the uninsured column. This is the downward “death spiral” that the petitioners hope will kill Obamacare. REACHING FOR IT

It was highly unusual and suspect that the Supreme Court reached for King v. Burwell, in which the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Virginia had approved the federal payment of subsidies. There had been no split rulings at the circuit level to cause the highest court to step in.

In a second challenge to the federal subsidies, Halbig v. Burwell, a three-judge panel of the Washington D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals had reached the opposite decision, ruling that the federal-run exchanges could not pay subsidies because of the seven words. But that court had vacated its own ruling, deciding that the case should be heard en banc, that is, by all the judges of that court.

That left King as the only ruling out there when the Supreme Court jumped the line, taking King for itself and thus aborting the D.C. court’s review of Halbig.

What was that about? Were the conservative justices wary that seven of D.C.’s eleven judges were appointed by Democratic presidents and might be disposed to rule in favor of the subsidies? If both cases were decided for the administration, the Supreme Court would have no justification to intervene.

This has happened before. It is a reminder of a similar moment when the justices reached well beyond a complaint about a corporate-funded political movie brought by the conservative advocacy organization Citizens United in order to advance a political agenda of unlimited campaign spending by corporations and unions. It’s hard not to suspect that the conservative justices again reached for a case because they wanted another crack at Obamacare. THE CHALLENGE

The King brief relies on the seven words in isolation, in proving that they were deliberate, that the federal government was to be denied issuing subsidies. The intent was to force states to set up their own exchanges.

The brief uses as evidence newspaper articles such as The New York Times saying in 2012 that “lawmakers assumed that every state would set up its own exchange” because “political reality” would deter them from turning down “billions” of free federal dollars. The brief cites Jonathan Gruber, an MIT professor and heavily paid consultant involved in crafting the healthcare bill, who had popped up in videos calling Americans “stupid” for not figuring out that the young and healthy insurance buyers would be paying for the old and sick, but relative to this case had said,

“If you’re a state and you don’t set up an Exchange, that means your citizens don’t get their tax credits.… I hope that that’s a blatant enough political reality that states will get their act together and realize there are billions of dollars at stake here in setting up these Exchanges, and that they’ll do it.”

Plaintiffs argue that it is not exceptional for the government to bestow its largesse only in return for states complying with a federal requirement; one need look no further than Medicaid within the Affordable Care Act itself. The states get 100% funding to cover new applicants for three years, but only if they expand the number of recipients.

Gruber notwithstanding, King’s contention that Congress deliberately attempted to coerce the states finds no corroboration from anyone in Congress. If denying subsidies to any state that failed to set up its own exchange had been the expressed intent, would we not have heard of furious arguments in Congress as the bill was formed and debated? Yet there was none. Jeffrey Toobin at the New Yorker says there were 53 meetings of the Senate Finance Committee, seven days of committee debate on amendments, and 25 consecutive days spent by the full Senate on the bill — “the second-longest session ever on a single piece of legislation” — with “similar marathons in the House”. Yet in all those deliberations there was no uproar because no one proposed that the subsidies were to be available only on the state exchanges. THE DEFENSE

The government argues that, given the Court’s own prior pronouncements, the full text of a statute must be taken into consideration — so-called “textualism”. “When we look at a provision of law, we look at the entire provision of the law,” said Justice Antonin Scalia early this year. “We try to make sense of the law as a whole”. Briefs cite his quotes as well as his emphasis on textualism in books he authored. “The interpretation of a law should do least violence to the text”, Scalia has written. In a post on SCOTUSblog, Yale Law School Professor Abbe Gluck said the “textualists” on the Court like Scalia “have spent three decades convincing judges of all political stripes” to adopt holistic readings of the law, giving priority to the full text. Says one brief, “Textualism demands that judges take seriously the statutory design (as gathered from the text) and avoid interpretations that would render the statute unworkable”.

The government points to several places in the law that contradict the seven words with wording that assumes the federal government will be paying subsidies. Examples:

It was the IRS that decided federal exchange clients would be eligible for subsidies. It is traditional that the interpretation by the agency of government charged with administering a law is given deference — the “Chevron” principle, named for an earlier precedent — one argument the government makes. The petitioners against the federal subsidies argue that the IRS does not have the authority to make so sweeping a revision of so major a statute. TRICKING THE STATES

The seven words occur in a section of the Act that spells out — in the tangled language familiar to do-it-yourself 1040 filers (e.g., “the amount equal to the lesser of” and “the excess, if any, of”) — the rules for who is entitled to a subsidy and how much. Briefs for the government raise a twofold question: first, why would a restriction of such enormity be buried in the formulas of an ancillary, nuts-and-bolts sub-section; and second, why would Congress knowingly build in a provision that has the power to sabotage its own law?

One of the briefs in support of the government was filed by 23 state attorneys from a mix of red and blue states that says the challengers’ position would “violate basic principles of cooperative federalism by surprising the states with a dramatic hidden consequence of their exchange election”. The brief assumes that each of the 34 states that elected not to set up an exchange must have deliberated their options, so would they all have decided to let the government run their exchange had they realized that subsidies would be denied to their people? “Nothing in the ACA provided clear notice of that risk”, which is a principle of cooperative federalism. “Retroactively imposing such a new condition now would upend the bargain the states thought they had struck”, says the brief. SWING VOTE

In the March hearing, Justice Anthony Kennedy, the crucial swing vote on the otherwise ideologically polarized court, had something else on his mind. King may only be a case of statutory interpretation, but wouldn’t there be constitutional issues if the Court ruled that subsidies were only available to residents of a state that had set up its own exchange? Doesn’t that effectively and unconstitutionally coerce the states to fall in line, Kennedy asked, because accepting so severe a penalty on its citizens would not be a “rational choice for a state to make”. And how to justify denying them insurance subsidies that other Americans would get? “There is a serious constitutional problem here if we adopt your position,” Kennedy said to Michael Carvin, representing the plaintiffs. That gave hope to those who want Obamacare to go forward undisturbed.

This factors into our prediction at the conclusion of the other article on the subject, for which see “If the Supreme Court Eviscerates Obamacare, Then What?”. But one is left to wonder whether the justices actually read the briefs, some of their questions being seemingly superficial. And do they consider the real world consequences of their actions, given that they are personally utterly unaffected. Samuel Alito contended in the hearing that, if the subsidies were denied, “going forward there would be no harm”.

Do any of them realize that, were they to lock onto seven words rather than the rest of the text, the disruption of millions losing their insurance after the disruption of gaining it would place the legitimacy of the Court at risk?

Finally, Jeffery Toobin’s fitting observation: “The great Supreme Court cases turn on the majestic ambiguities embedded in the Constitution…. Instead of grandeur, there is a smallness about this lawsuit in every way except in the stakes riding on its outcome”.

mention federal exchanges? Or do other sections of the statute show that phrase to be only a lapse in wording?![]() The same section that purportedly limits subsidies to states that create their own exchanges calls for both state and government exchanges to provide the IRS with the information it needs to administer the subsidies (they take the form of tax credits). Why would the government exchanges be required to provide that information if none of its customers are eligible for such credits?

The same section that purportedly limits subsidies to states that create their own exchanges calls for both state and government exchanges to provide the IRS with the information it needs to administer the subsidies (they take the form of tax credits). Why would the government exchanges be required to provide that information if none of its customers are eligible for such credits?![]() The government contends that an exchange it creates for a state is “established by the state”, with the government acting in its behalf. Section 1321 prescribes that Health and Human Services “shall…establish and operate such Exchange within the State”. That wording treats the federal exchanges not as federal but as surrogate state exchanges.

The government contends that an exchange it creates for a state is “established by the state”, with the government acting in its behalf. Section 1321 prescribes that Health and Human Services “shall…establish and operate such Exchange within the State”. That wording treats the federal exchanges not as federal but as surrogate state exchanges.![]() Other sections concerning state exchanges make no separate mention of parallel federal exchanges, implying that the Act considers them to be one and the same and that subsidies are therefore intended for both.

Other sections concerning state exchanges make no separate mention of parallel federal exchanges, implying that the Act considers them to be one and the same and that subsidies are therefore intended for both.![]() Section 1312(f) stipulates that only a person who “resides in the State that established the Exchange” can purchase on an exchange. If a federal exchange established for a state is not considered a state exchange, then that state can have no customers, says this rule. The clear intention is that all such exchanges are considered by the Act as state exchanges and therefore eligible for subsidies.

Section 1312(f) stipulates that only a person who “resides in the State that established the Exchange” can purchase on an exchange. If a federal exchange established for a state is not considered a state exchange, then that state can have no customers, says this rule. The clear intention is that all such exchanges are considered by the Act as state exchanges and therefore eligible for subsidies.![]() Three times in the Act, “Exchange” is defined as being a state exchange, the point being that there is no federal exchange, only subsidy-eligible state exchanges run by the federal government.

Three times in the Act, “Exchange” is defined as being a state exchange, the point being that there is no federal exchange, only subsidy-eligible state exchanges run by the federal government.