By the People, For the People? But We Don’t Seem to be Getting the Breaks

Corporations, though, are doing just fine Jun 16 2018We like to boast that we are a free people, and for the most part we are. But the pithy warning that "eternal vigilance is the price of liberty" may not have been passed on to new generations all that successfully because they don't seem to notice the many ways congress, the courts, the president are finding ways to put the cuffs on individual freedom and hand the keys to corporations.

Donald Trump won the presidency with pledges to help working-class Americans

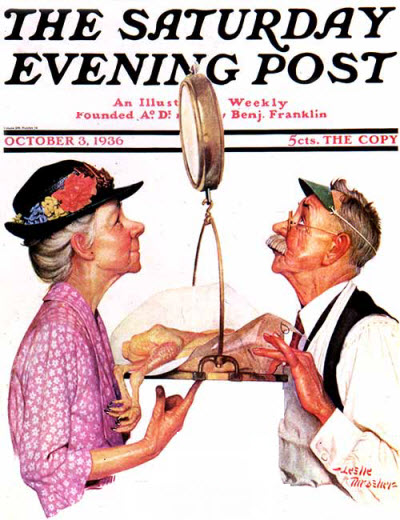

You'd think there's a finger on the scale.

— the "forgotten men and women" who have seen themselves stranded economically while the wealthy reap all the gains — yet we watch the paradox of the many actions of the Trump administration, the Republican-controlled Congress and the Supreme Court that steadily squeeze the rights and future of we the people. Here's a rundown:

In May the conservatives on the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that companies can require employees to submit to arbitration in wage disputes and can deny their right to band together in class action suits. The latter ban on its own would have left employees to take on corporations as individuals, one-by-one, having to bear unaffordable legal expenses singly instead of as a group. The former, forced arbitration, could affect some 25 million workers under contract and an untold number of current employees whom corporations might now require to sign away their rights if they want to keep their jobs. New hires can expect to be forced to sign agreements restricting them to arbitration as a condition of employment.

Trump appointee Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion, in which he says the Court is following a prior federal law that favors arbitration for its "speed, simplicity and inexpensiveness". It is up to legislatures to make changes, he says. In her dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg pointed out what an oppressive problem arbitration has become for the individual, writing that in 1992 only 2% of non-unionized employers imposed mandatory arbitration on workers; that has become 54% today.

Under arbitration a person with a complaint goes, along with the corporation's representative, before a single individual, usually, from a firm that specializes in judging disputes. The arbitrator hears both sides and renders a binding decision. So much simpler and economical than a court trial. Problem is, a corporation typically hires a single arbitration firm to handle all its disputes. If that firm decides against the corporation more than a token number of times, it is sure to lose the corporation as a client. A “Frontline” documentary on PBS showed the example of First USA, a company that handles credit card transactions. (In their case not the wage disputes of the Court's ruling, but it's the same dynamic.) First USA had won 19,618 cases in arbitration. How many cases did card users win? 87. That's how the Court has stacked the deck against American workers.

ball and chainDoubling down against employees is the proliferation of non-compete clauses in hiring contracts. Once applied only to highest value employees privy to a company's proprietary knowledge, they have spread as low as fast-food chains to keep workers manacled to their jobs like indentured servants, unable to accept higher paying offers from fast-food competitors even though no business secrets are at issue. Some 30 million workers are now covered by non-competes says the Treasury Department — 1 of every 5 of us — and 14% of them earn less than $40,000 a year. Some contracts range far beyond the job description itself, blocking an employee from taking a job in any other field for which his or her skills might apply. What has happened to laws that once voided business contracts that sought to "deprive of livelihood"? And where is the justice of a company preventing a former employee from taking a job with competitors without paying the employee for not doing so? Non-compete clauses without compensation should be unenforceable.

California stands out as one state that makes non-compete clauses moot. A few states are following suit. But a practice that puts America's workers in leg irons needs a national crackdown. The Obama administration had pushed Congress to limit the practice. At its simplest a law could establish a pay threshold below which a worker surely has nothing to do with corporate secrets. It's an ideal cause for Trump to take up: helping the forgotten worker get a leg up in life.

businesses need protection, tooThe Consumer Finance Protection Bureau was one piece of the enormous 2010 financial reform law known as Dodd-Frank. Its purpose was to act as a counterweight to the power of vast corporations, to protect the public from unfair practices by banks and credit card companies; mortgage, auto, and payday lenders; and financial grifters in general. Republicans hate the CFPB. They call it government overreach with too much power over business, a "protection racket" says National Review that shakes down corporations for millions, is accountable to no one, and has a degree of independence they say is unconstitutional. This is as was intended: To keep CFPB free of political influence it is funded by the Federal Reserve, there is no congressional oversight, and its director cannot be removed by even the president, except for cause.

Under Obama appointee Richard Cordray, the agency had collected $12 billion from multiple financial companies as penalties for wronging consumers, most notably Wells Fargo for having staff create more than two million accounts in customers' names without their knowledge and then charging them fees. But as the brainchild of one of President Trump's most nettlesome critics, Elizabeth Warren, the CFPB was certainly a target for the president when Cordray quit to run for governor of Ohio.

The law stipulates that the deputy director "shall…serve as acting Director in the absence or unavailability of the Director" but Trump brushed aside the deputy and told his budget director Mick Mulvaney to take over. Mulvaney had called the bureau a "joke…in a sick, sad kind of way". He would be "like a mosquito in a nudist colony", said legislative affairs director Marc Short. A federal court has allowed the executive branch to usurp control of the bureau in keeping with the 1998 Federal Vacancies Reform Act, but the move contravenes the Dodd-Frank law, and the matter is still before the courts.

Meanwhile, there is a time limit that ends June 22 for how long a government official can serve in a dual role. But in the brief time allotted him, Mulvaney has worked at flank speed to reverse what Cordray set in motion. Immediately on taking over he froze enforcement proceedings and rule-making; halted hiring; stopped the collection of monitoring data from banks; and shifted the emphasis to first evaluating the cost of a proposed action before deciding to enforce. For Mulvaney, in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece, the CFPB's protection is not just for consumers. Rather it is for…

"those who use credit cards and those who provide credit; those who take out loans and those who make them; those who buy cars and those who sell them."

How did that turn out?![]() Barely 48 hours after taking over, he had the CFPB cancel an $8 million fine against an Ohio mortgage company that the courts agreed had misled more than 100,000 customers.

Barely 48 hours after taking over, he had the CFPB cancel an $8 million fine against an Ohio mortgage company that the courts agreed had misled more than 100,000 customers.

![]() In January he dropped a case against four lending companies preying on an Indian tribe with interest charges that annualized to 950%.

In January he dropped a case against four lending companies preying on an Indian tribe with interest charges that annualized to 950%.

![]() Claiming it's no more than simple reorganization, Mulvaney dismantled the group that went after predatory student loan collecting, merging its personnel into the agency's office of financial education. That has caused consumer advocates to fear that enforcement would evaporate, replaced by simply publishing advice to students about their rights. Americans are strapped by $1.5 trillion in student debt and the agency had clawed back about $750 million from lenders under Cordray. Now, the concern is that a major enforcement case against Navient, the country's largest student debt collector, for steering low income kids into high-cost programs, will be snuffed.

Claiming it's no more than simple reorganization, Mulvaney dismantled the group that went after predatory student loan collecting, merging its personnel into the agency's office of financial education. That has caused consumer advocates to fear that enforcement would evaporate, replaced by simply publishing advice to students about their rights. Americans are strapped by $1.5 trillion in student debt and the agency had clawed back about $750 million from lenders under Cordray. Now, the concern is that a major enforcement case against Navient, the country's largest student debt collector, for steering low income kids into high-cost programs, will be snuffed.

![]() Mulvaney has shut down public access to a database where consumers can register complaints against banks, credit card processors, etc. Since its inception in 2011, it has attracted 1.5 million consumer complaints. Businesses say the gripes shouldn't be made public because haven't been verified by some arbiter, presumably themselves. Holding up a copy of the Dodd-Frank law at a banking industry conference, Mulvaney said, "I don't see anything in here that says I have to run a Yelp for financial services sponsored by the federal government". Corporations, through advertising and public relations, have the money and access to present themselves as public benefactors. Mulvaney has chosen to shut off an avenue where the public can make their voices heard and warn others in a searchable database. Now, only companies will have access to what consumers have to say about them.

Mulvaney has shut down public access to a database where consumers can register complaints against banks, credit card processors, etc. Since its inception in 2011, it has attracted 1.5 million consumer complaints. Businesses say the gripes shouldn't be made public because haven't been verified by some arbiter, presumably themselves. Holding up a copy of the Dodd-Frank law at a banking industry conference, Mulvaney said, "I don't see anything in here that says I have to run a Yelp for financial services sponsored by the federal government". Corporations, through advertising and public relations, have the money and access to present themselves as public benefactors. Mulvaney has chosen to shut off an avenue where the public can make their voices heard and warn others in a searchable database. Now, only companies will have access to what consumers have to say about them.

A case against Wells Fargo begun under Cordray that led to a $1 billion fine did go forward in April, though, possibly because it had been much in the headlines.

Mulvaney has gone before Congress to ask that Dodd-Frank be revised to place the CFPB under the executive branch, with oversight by Congress, which would destroy the autonomy of its deliberate design and make its consumer protections subject to whichever way the political winds blow.

left behindBefore Mulvaney's arrival, the bureau had taken years to develop rules to rein in the usurious practices of payday lenders. Issuing some $46 billion in loans a year from more storefronts than there are McDonald's, they collect $7 billion from 12 million Americans whose paychecks fall short of living expenses and who have no other credit sources. They turn to the "short-term" lenders, as the industry prefers to characterize itself, who often lend on terms that assure borrowers will fail. Many can only pay back a portion of their debt, and the pileup of interest charges — often the equivalent of 300% to 400% a year — plunges them ever deeper into a debt than far exceeds the original loan. Fifteen states already ban payday lenders. For the rest, the new rule would require lenders to run a credit check to ascertain ability to repay. And it limits rollovers, by which people take out new loans to pay for the old.

As you might expect, given our theme, One of Mulvaney's first acts was to roll back the new rules, allowing predatory practices to roll on.

As director of the other consumer protection unit, part of the Federal Trade Commission, the president has just chosen Andrew Smith, a lawyer who in 2012 defended a payday lending company founded by a convicted racketeer in a case prosecuted by the FTC itself that resulted in a court-ordered settlement of $1.3 billion. More recently, he has represented Facebook, Uber, and Equifax — all with pending matters before the FTC.

skin in the gameIn April, the Senate overturned an Obama-years rule set by the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau that prevented auto loan lenders from discriminating against minorities by charging them higher rates. The House passed the rollback in May, freeing banks to use discriminatory pricing based on race or ethnicity.

work ethicRepublicans in the House could vote for a new farm bill that would impose work requirements for recipients of food stamps, dropping maybe two million from the program according to the liberal-leaning Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. Trump has said, "We can lift our citizens from welfare to work, from dependence to independence, and from poverty to prosperity." There is no evidence to support that cheerful a prognosis. Reform under President Clinton cut welfare recipients from 68% of the poor to 23% (and benefits have declined by a fifth since), but those taken off the rolls found themselves stuck in the low-pay labor market. Still, in an economy where there are now more job openings than workers to fill them, says the Wall Street Journal, nudging the able-bodied to take a job and perhaps get off taxpayer food subsidies is not unreasonable.

Very different is the Trump administration's allowing the states to attach a work requirement in return for receiving Medicaid benefits. What's the connection? Do they expect the newly-employed to be able to afford health insurance on their own, in which case it would be work in return for loss of Medicaid? Hundreds of thousands of poor Americans are expected to lose their health insurance as states perform the triage of deciding who among the non-working aren't too old, or not too ill, or not trying hard enough to find a job and thus should be stripped of Medicaid.

At one end is Bernie Sanders promoting Medicare for All without concern for how we can possibly pay for it. At the other extreme are states looking for a way to save money by casting their poorest adrift. The partisan divide cannot get any wider than that.

Please subscribe if you haven't, or post a comment below about this article, or

click here to go to our front page.