For decades in America, corporations have followed the precept set down by the University of Chicago school of economists, led by Nobel recipient Milton Friedman, that the sole calling of a corporation is to maximize value for its shareholders. That profit at all cost

could lead to a welter of harm and hardship to people and the environment were unfortunate but must not be allowed to interfere with that goal.

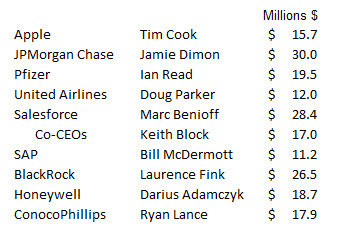

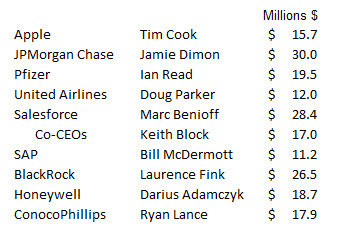

In words if not yet in deeds, that changed abruptly when the Business Roundtable, its membership the chief executive officers of large U.S. corporations, took full-page ads in the major newspapers to issue a “Statement of the Purpose of a Corporation”, prefaced by reminders that freedom, liberty, and a free market economy have been a “critical engine” to the nation’s success. The new doctrine bore the signatures of 181 CEOs of major companies from a cross-section of industry such as of Apple, JPMorgan Chase, Pfizer, United Airlines, Salesforce, SAP, BlackRock, Honeywell, and ConocoPhillips.

The Statement consists of five commitments, two of which are taken up by what one would think are nothing new — “Delivering value to our Customers” and “Generating long-term value for Shareholders”, unless “long-term” deliberately signals a shift away from the obsession with quarterly profits. The others pledge ethical and fair dealing with suppliers, protecting the environment of local communities, and investing in employees with fair compensation, benefits, and training. There is no mention of unions.

To serve only its investors — what it called “shareholder primacy” — has been the Roundtable’s official position since 1997. So what explains the sudden volte-face by the business community that corporations should change their outlook and look for ways to better benefit all with whom they deal? The ad mentions that “many Americans are struggling”, that “too often hard work is not rewarded”, and that “the rapid pace of change” is leaving workers behind, but more factors than those have been building, primary among them the discontent with huge disparities in wealth between those at the top and the rest. There is the disillusionment with a culture that demands a college education for employment only to leave us with a lifetime of student loan debt, a worry that robots and now artificial intelligence will take our jobs, and the fear that climate change is going to make life more unpredictable and dangerous. Then, too, the newer generations, put off by the greed of corporate management, have developed an attraction for socialism over capitalism as a scheme they believe better contributes to the good of society.

Surely the corporate capitalists weren’t responding to Elizabeth Warren, although she got the drop on them a year ago when she introduced the Accountable Capitalism Act, its premise being that corporations that claim the legal rights of personhood should be legally required to accept the moral obligations of personhood. Corporations are treated as persons under the law so that they can sue and be sued, but their personhood was extended by a good measure when the Supreme Court in 2014 decided in favor of the Hobby Lobby corporation, giving that family-owned business a special exemption from paying for insurance for employees that includes contraceptives. Doing so, went the plaintiffs argument, offended the religious sensitivities of the corporation. You read that correctly.

And the notion that corporations owe to society hearkens back to a 2012 kerfuffle when, campaigning against Mitt Romney, President Obama gaffed, “If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen”. It was inartfully phrased but part of a full talk on the subject. A bit of its context made clear his meaning:

“If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.”

Nevertheless, the Romney campaign posted a 15-second video that showed the president saying five times over, “If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that”.

ramifications

The new socially conscious dedication is certainly welcome, but raises many questions. If a company decides to close a plant and move production offshore, how will its CEO make the case that this somehow supports the community that the corporation is abandoning? Will these businesses continue to hire lobbyists to press for legislation and fund politicians who will do their bidding when benefits to the corporation may mean harm to the nation? Will they continue to contribute to superPACs, or honorably refuse to participate in this execrable perversion of democracy? Will they withdraw harmful products from the market? Will they end the tax avoidance maneuvers of shifting profits offshore and pay more into this country’s coffers, or is that too broad a definition of “communities in which we work”? Do all of them have the consent of their boards or will their directors, wary of stockholder suits, have quite a different take? Will they adopt the German plan of having a worker representative join those boards?

Many questions. A big one is what will they do about their own pay packages? The usual compensation plan is a mix of annual performance bonus, stock options, incentive targets geared to short term results and the stock’s price, and outright grants of stock often linked to performance over typically three years. Does the manifesto’s quiet mention of “generating long-term value for shareholders” mean not only will these CEOs steer away from satisfying Wall Street’s insatiable demand for short-term gains but also realign compensation to long-term results such as 10-year time frames?

skepticism entitled

Considering the staggering amounts paid to so many CEOs and their upper management and what that has done to increase America’s income inequality, it is reasonable to question whether they’ve had a sudden epiphany on the road to Damascus or whether this is little more that a public relations ploy to deflect negative publicity of their own avarice. After all, they’ve only come to this turning point after they’ve had their boards serve up ever-increasing pay packages for years, and for many the value of the stock holdings in their companies has been boosted by buybacks. More on that in a moment.

Just last year, the biggest 500 corporations in the U.S set total CEO pay records for the fourth year in a row, with compensation at the median registering $12.4 million. The median of the 200 highest-paid CEOs in America was $18.6 million, up by $1.1 million or 6.3% from the year before. That’s twice the 3.2% increase enjoyed by the average American worker. Their pay went up by 84 cents an hour. CEO pay went up by more like $500 an hour. The median CEO got $1.5 million every month.

We cite median because Elon Musk made average pay unusable. He got $2.284 billion in 2018. The new disclosure rule that requires CEO pay to be compared with that of its employees revealed that Musk was paid 40,668 times what the median Tesla worker gets.

That list above of corporations whose CEOs are Roundtable members? As a sampling, here’s what they were paid in total in 2018 — cash, stock, etc.:

the buyback bonanza

Beyond these lavish compensation arrangements, many of the CEOs of the Roundtable and their directors have added a favorite source of enrichment, launching the biggest stock buyback campaigns we’ve yet seen. Not only was the corporate tax rate slashed from 35% to 21% beginning last year, but companies were given further tax discounts to induce them to return an estimated $2.6 trillion of profits held overseas — tax rates of 15.5% for cash and 8% for less liquid assets. So corporations have been awash with cash. The stock buyback surge started earlier than the tax cuts — since 2013 companies have poured $4.2 trillion into buybacks — but it peaked last year with $1 trillion authorized by corporate boards.

Your corporate finance textbook will say that a stock buyback is merely returning money to investors, “a natural function of capital markets”, says Dimon of JPMorgan Chase. “The money doesn’t vanish”, says Lloyd Blankfein, the former chief of investment bank Goldman Sachs. “It gets reinvested in higher growth businesses that boost the economy and jobs”. The Wall Street Journal‘s editorial page says everyone needs a “refresher course” that “repurchasing shares is simply one way a company can return cash to owners if it lacks better ideas for investment”.

Well and good, but our point is that major corporation CEOs have been a self-serving lot in a number of ways, so there’s a back story to buybacks.

First, they’ve become favorites for CEOs and their directors because shareholders pay tax only on profit, if any, and that at low capital gains rates, whereas the full amount of dividends, the more traditional way to reward investors, are taxed as ordinary income. If those of the Roundtable CEOs who engineered buybacks were concerned for the general good, why the choice of the lowest tax route to return capital to shareholders?

CEOs and directors have been served up with large portions of stock as often the biggest slice of their compensation. In a buyback, look what magically happens to their stock holdings. A buyback reduces the number of shares at large. Thus, the unchanged value of the company is divided among fewer shares, increasing the value of each share. The market sees the earnings per share rise — a key metric — and bids up the value of each share held by those corporate officers. Additionally, the mere announcement of a buyback causes the share price to rise in anticipation, and those CEOs and directors often unload big chunks of their own stock. Their decision to have their company buy back its own shares is a vote for their own gain.

As the Journal says, a company may see little else to do with the money. There is a growing malaise that says that may be a more general condition than we’d like to admit. Robert Gordon’s 2017 book, “The Rise and Fall of American Growth”, brought that harshly to light, arguing that after a century of extraordinary invention and development — from electric lighting to color television on giant screens, from Model T autos to supersonic jets — there may not be much left. That’s debatable, of course. But we don’t make things, and what is there new to make anyway that has the potential of universal public take-up, like the smartphones which are reaching their peak?

The Internet giants — Facebook, Google, Twitter, etc. — are all almost entirely supported by the advertising of others. Big popular successes lose breathtaking amounts of money — Uber, WeWork, others. Corporations see this and perhaps have become too risk-averse to attempt what could be next, with the result summed up in Peter Theil’s quip, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters”.

So some CEOs may have been doing the responsible thing by returning money to shareholders, but unless you subscribe to the nothing left to do ethos, others have been short-changing their companies’ prospects by draining billions in capital from their balance sheets, thereby threatening the competitive prospects of American industry.

Or, instead of buybacks, they might have done more — permanent pay raises instead of one-time bonuses, paid sick leave, child care subsidies — for those employees that they now profess to be so concerned about in their proclamation.

Sep 12 2019 | Posted in

Zeitgeist |

Read More »