Biden’s Ambitious Social Program Stumbles Toward the Finish Line

[Updated November 20]: That President Joe Biden’s progressive social and climate legislation has been sharply cut back and reconfigured from the $3.5 trillion that was originally proposed comes as no surprise. That he and Democrats in Congress embarked on so colossally ambitious a program, along with $1.2 trillion for infrastructure, with only a tie-breaker vote in the Senate, three votes to spare in the House, and riven by factions of centrists and progressives in their own party, should have signaled folly from the start.

And yet, Democrats carried on wishfully for months, making no early warning

Democratic Senators Joe Manchin (WVa) and Kyrsten Sinema (Ariz) presented themselves as obstacles at the outset. Then, the issue was getting rid of the filibuster. We reported their intransigence as far back as March (“How the Filibuster Threatens Biden’s Presidency”), with Manchin going on Fox News (that’s not a typo) to say “I will not vote to do that”. Sinema was equally emphatic, telling Oklahoma Congressman James Lankford, “I would always oppose efforts to eliminate the filibuster”.

The worry that the infrastructure bill would be filibustered didn’t happen, but their position on the filibuster now carries over to the two voting rights bills which their obstinacy threatens with extinction.

In August, the infrastructure package was passed in the Senate by a wide, bipartisan 69-to-30 margin. Enough Republicans were enthusiastic about bringing home money and jobs to their states that they brushed aside the harangues and threats from Donald Trump against voting for it. He had promised infrastructure legislation as part of his “I alone can fix it” presidency but had so failed to do anything that “infrastructure week” became a joke. He now called fellow Republicans who voted for the bill “weak, foolish, and dumb RINOs” (Republicans in name only) for following through on what he had pledged to do. near fatal embrace

The biggest hurdle then came from the progressives in the House, a 100-or-so member caucus led by Washington state’s Pramila Jayapal. The progressives have insisted that the giant $3.5 trillion social spending bill first be passed in the House before they will vote on infrastructure. Jayapal believes that if infrastructure were passed first and on its own, the social and climate spending bill would simply die. The risk was that in a standoff both would.

Centrists in the House object to what the huge size does to the national debt, already at $28 trillion. And Speaker Nancy Pelosi has to look over at the Senate where the intractable duo of Manchin and SInema have multiple objections. The bill would use the “reconciliation” process that rules out filibustering and requires only a simple majority for passage, but no point passing the bill in the House if the Senate is short the full 50 votes (plus Kamala Harris’s tie-breaker) needed.

Having discovered from their filibuster stance how much power they have in running the Biden administration, Sinema and Manchin have come up with a profusion of demands. Their objections to the $3.5 price tag has led to an agreement to a cost hovering around $2 trillion for Manchin, but the Arizona Garbo won’t commit to anything, basking in the plenitude of media profiles that wonder at the mystery woman’s elusiveness. After meeting with her, House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard Neal (D-Mass.) said her three priorities were a child tax credit, paid leave programs, and a tax credit for renewable energy programs, yet elsewhere she said she wanted $100 billion cut from the climate program.

Ms Sinema has come up with new demands at this last minute. The Wall Street Journal reported that Sinema “has told lobbyists that she is opposed to any increase” in taxes on capital gains, high-income individuals or businesses. Running counter to virtually universal Democratic policy and contradicting her own vote against the 2017 tax cuts when in the House, this would seem to be an act of deliberate sabotage. Tax increases are essential to paying for the Build Back Better plan. Bills passed by reconciliation expire, usually after 10 years. Their provisions cease, or revert to the status quo ante of the years before their passage. Senate rules say that a reconciliation bill must pay for itself. More specifically, while it can be in the red in some years, it must show, as analyzed (“scored”) by the Congressional Budget Office, that it will not increase the deficit beyond its time span. The three tax changes that Sinema objects to have all along been essential to Biden to pay for his agenda. He has persistently said, as he did again as late as this month in Michigan, that “The cost of these bills, in terms of adding to the deficit, is zero. Zero. Zero.” That’s a highly dubious claim even with the tax increases he proposed and a fantasy if Sinema withholds her vote. Already dropped from Biden’s plan was a tax at time of death on the gain in value of assets that otherwise transfer tax-free to inheritors. As always, this badly needed fix to the inequitable tax code was abandoned when Democrats in Iowa and Montana revolted, saying it would hurt family farms, even though Biden was open to exempting farms worth less than $25 million and stretching tax payments over fifteen years for those above. The reduction to $2 trillion at least means less money needs to be found to pay for it, but Senator Sinema’s remarks set off a scramble to find other sources of revenue. What happened to funding the IRS to pursue tax cheats? The proposed cost was $80 billion, but it was projected to bring in as much as $700 billion from enforcement. If added to the social and climate bill, that theoretical gain could be counted as payment for Biden’s master plan, but it has disappeared as a topic. Of course, Sinema objects to that, too. So do some centrist Democrats who perhaps think the IRS could force their wealthy campaign donors to pay up. There is the proposal to permit Medicare to negotiate drug costs rather than accept whatever pharmaceutical companies charge. Drug charges in the U.S. run to triple what companies charge in OECD countries. Yet Republicans in the George W. Bush years passed a law that forbade Medicare from negotiating prices to ensure that hefty campaign donations from pharma companies would keep coming. A solid 88% of voters want that repealed so that the federal government can be free to negotiate, even 77% of Republicans. The freedom of Medicare to cut deals could save taxpayers half a trillion dollars over a decade. But three House Democrats don’t like the idea, and Ms Sinema has decided she doesn’t like it either, even though she campaigned on lowering drug costs. Over her political career the senator has taken in some half a million dollars from pharmaceutical PACs and direct contributions from corporate executives. The $120,000 in support that her campaign received in 2019 and 2020 just may have turned her head. It is the same with the three House Democrats. Altogether, the four of them have collected $2 million from drug companies.

What about a carbon tax — long thought the best answer to curbing emissions? It would raise a ton of money to offset the Biden agenda’s cost, but Manchin and Senator Jon Tester (Mont.),

Nevertheless, and despite the three House Democrats, Ms Pelosi emerged from a White House breakfast with the president, pretty much as this is written, to say that a deal is “very possible”, that 90% of the bill is agreed to and written. the cupboard almost bare

So what’s the plan now to recover enough funding to pretend to cover the cost of the bill? Already dropped from Biden’s plan was a tax at time of death on the gain in value of assets that otherwise transfer tax-free to inheritors. As always, this badly needed fix to the inequitable tax code was abandoned when Democrats in Iowa and Montana revolted, saying it would hurt family farms, even though Biden was open to exempting farms worth less than $25 million and stretching tax payments over fifteen years for those above. So the White House in desperation has at this last minute turned to Elizabeth Warren’s dream of taxing the accumulated wealth of the richest among us. The White House is looking at ideas to go after the 700 most moneyed American families, the wealthiest 0.0002 %.

Unlike the simplicity of tax brackets, the proposal promises unwieldy complexity. Billionaires and households earning more than $100 million in income three years in a row would be subject to annual taxes on the increased value of assets such as stocks (net of paper losses) regardless of whether they sell those assets. The plan would also somehow tax assets that are not easily tradable, such as real estate.

What does Sinema have to say about that? “Officials and other senior Democrats are cautiously optimistic”, says one news break, but the real answer is, no one knows. What’s left and what’s gone?

It is difficult and imprecise to deduce what remains in the $2 trillion bill; negotiators have kept it vague, so this is sketchy. Best guesses:

Our question is: What will make one account look any different to the IRS than any other with the same level of activity? Banks are fuming, and not just from asking them to spy on their customers. Inevitably, amendments will exempt other types of inflow and outflow. How are financial institutions to develop code to identify and exclude them? Banks foresee a dreadful year-end horror, mainframes smoking like like bitcoin miners to sift and tally a hundred million-plus accounts. The White House view of banks’ complaints was made clear by House press secretary Jen Psaki: “It’s about big banks deciding to protect wealthiest Americans that get away with not paying the taxes they owe by fighting this common-sense solution.” Presidents and legislators, of course, have no clue of the effect of their whimsy out in the real world. “Stay tuned” fits this story.

Bleak house?

modifications to their Utopian scheme, as if dissidents among them would surely be placated or not be foolish enough to block the agenda. The $1.9 trillion bill (now named the Build Back Better Act) passed the House but intractable obstacles await in the Senate.

Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia,

and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona. Mum’s the word.

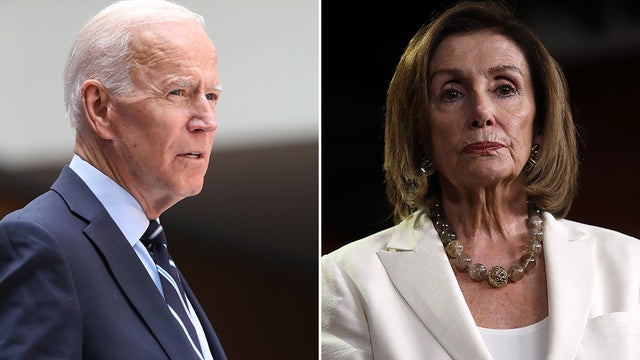

The president and Nancy Pelosi are in a high wire act.

both from coal-producing states, will have none of that.![]() Universal pre-K schooling for kids ages 3 to 4 is still alive as is the extension of the child tax credit, although probably reduced in amount and/or duration. Together the objective is to cure the diminished presence of women in the workforce as a key component in invigorating the economy. Having to pay for day care makes discouragingly little what is left in a paycheck weighed against the effort and time spent working, Additionally, these programs cut child poverty dramatically. Early education has been shown in actual case studies — in which groups have been tracked through decades — that life outcomes are improved.

Universal pre-K schooling for kids ages 3 to 4 is still alive as is the extension of the child tax credit, although probably reduced in amount and/or duration. Together the objective is to cure the diminished presence of women in the workforce as a key component in invigorating the economy. Having to pay for day care makes discouragingly little what is left in a paycheck weighed against the effort and time spent working, Additionally, these programs cut child poverty dramatically. Early education has been shown in actual case studies — in which groups have been tracked through decades — that life outcomes are improved.![]() Paid family leave, originally 12 weeks, has been scaled back to four, that is, if Mr. Manchin goes along, as he has expressed misgivings about the U.S. adopting what is commonplace in all other developed nations. He has said he wants to avoid “changing our whole society to an entitlement mentality”.

Paid family leave, originally 12 weeks, has been scaled back to four, that is, if Mr. Manchin goes along, as he has expressed misgivings about the U.S. adopting what is commonplace in all other developed nations. He has said he wants to avoid “changing our whole society to an entitlement mentality”.![]() Two years of tuition-free community college have been pulled from the bill.

Two years of tuition-free community college have been pulled from the bill.![]() The president’s provisions to combat climate change are surely retained else he would look hopelessly ineffectual. But Manchin dealt the program a major blow when he refused to vote for a bill that contains the Clean Energy Performance Program (CEPP). That provision calls for companies to be penalized for failure to adopt renewable energy methods to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. The senator (along with John Tester of Wyoming) represents a coal-producing state that, in West Virginia’s case, produces almost all its energy in coal-fired plants and would be heavily penalized under the statute. Removal of CEPP, which of course applies nationwide, is estimated to cut a third of Build Back Better’s climate impact. That amounts to a failure to curtail as much as 700 million metric tons of emissions a year, according to Energy Innovation, a nonpartisan energy and climate policy think tank, which poses a serious threat to the president’s pledge to to halve emissions by 2030.

The president’s provisions to combat climate change are surely retained else he would look hopelessly ineffectual. But Manchin dealt the program a major blow when he refused to vote for a bill that contains the Clean Energy Performance Program (CEPP). That provision calls for companies to be penalized for failure to adopt renewable energy methods to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. The senator (along with John Tester of Wyoming) represents a coal-producing state that, in West Virginia’s case, produces almost all its energy in coal-fired plants and would be heavily penalized under the statute. Removal of CEPP, which of course applies nationwide, is estimated to cut a third of Build Back Better’s climate impact. That amounts to a failure to curtail as much as 700 million metric tons of emissions a year, according to Energy Innovation, a nonpartisan energy and climate policy think tank, which poses a serious threat to the president’s pledge to to halve emissions by 2030.![]() All is quiet about whether the proposal to assist the IRS to identify tax cheats has survived intense blow back from banks. Authored by Senators Elizabeth Warren (Mass.) and Ron Wyden (Ore.), the measure would require banks and other financial businesses that deal in money transfers to annually report customer accounts that show inflow and outflow transactions other than wages that exceed $10,000. That’s for an entire year, which works out to be, well, just about everyone (just think of credit card transactions for food, gas, etc.) Originally they proposed a ludicrous $600 with no mention of the wage exemption.

All is quiet about whether the proposal to assist the IRS to identify tax cheats has survived intense blow back from banks. Authored by Senators Elizabeth Warren (Mass.) and Ron Wyden (Ore.), the measure would require banks and other financial businesses that deal in money transfers to annually report customer accounts that show inflow and outflow transactions other than wages that exceed $10,000. That’s for an entire year, which works out to be, well, just about everyone (just think of credit card transactions for food, gas, etc.) Originally they proposed a ludicrous $600 with no mention of the wage exemption.