Four Countries Out to Make U.S. a Bit Player on the World Stage

Remember the Nineties? The Soviet Union had broken apart, ending the long Cold War. The first McDonald’s opened in Moscow; Russians waited in long lines to sample America’s famous fast food. American corporations poured in. Germany was reunified. Peace in our time.

Yes, North Korea persisted in threatening South Korea, but with only artillery. China was a poor country that could not begin its ascent until 1999 when it was accepted into the World Trade Organization. It “creates a win-win result for both countries”, said President Clinton, who might like to have that back. We sanctioned Iran for sponsoring terrorism, but if they had begun exploring nuclear for other than peaceful purposes, they managed to keep it a secret.

Democracy was peaking. There were still fax machines and no smart phones, the Internet was stirring, the browser and the search “engine” were invented, we watched “Seinfeld”. The coming century showed great promise, if only we could get past those pesky computers seizing up on Y2K. upheaval

A quarter century later, a stunning reversal. In one after another country a populist movement has arisen that pulls in the economically left behind and gives rise to a new age of the strongman. The United States finds itself confronted by four countries — Russia, Iran, North Korea, China — intent on bringing down the western alliance and on establishing their own spheres of influence by diminishing the American presence in the world. They share the view that the U.S. is decadent and corrupt, a declining hegemon, a paper tiger that cannot be trusted to keep its word.

What brought about that evolution is its own story. It is job enough here to look at the current alignment of each of our principal adversaries. Europe on the edge

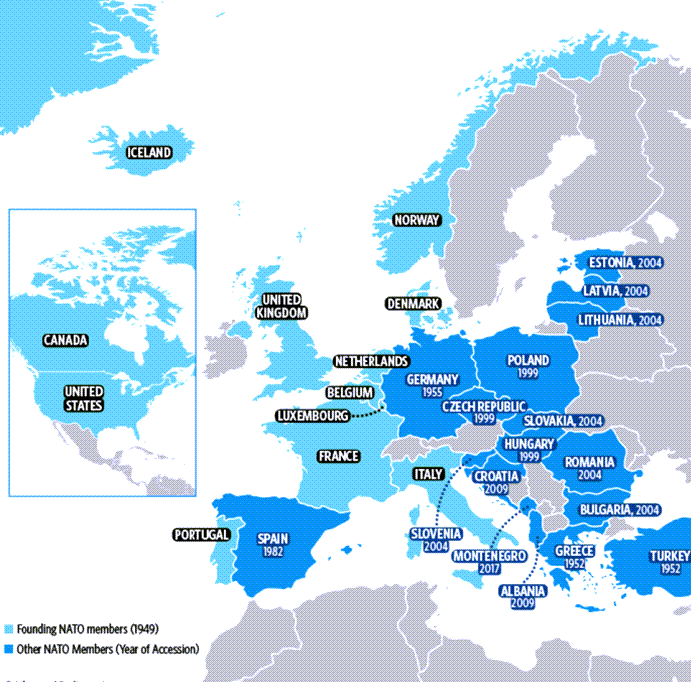

If Russia occupies Ukraine, a scenario we need to assume, this will move the pieces on the chessboard of Europe. The map shows that Ukraine and Belarus have

But Belarus is on its way to becoming a vassal of Russia. Dictator Alexander Lukashenko welcomed Russian police to quell demonstrations that protested the rigged 2020 election. This February he opened the door to 30,000 Russian troops and weaponry that are likely to be permanently encamped there when not in Ukraine. Belarus sees itself as entirely reliant on Russia for protection, so Putin will expect the freedom to move his military about at will.

Moldova will surely tempt Putin. It is expected that if Russia succeeds in taking Odessa and the whole southern rim of Ukraine, the Russians will keep moving west. That sets the stage for what would then happen. These newly annexed countries border NATO member states. The buffer will be gone. Russia will be able to press its military up against the western edge which, out of Putin’s paranoia of NATO, he is sure to do.

That will bring about realignment down the swath of eastern Europe as countries on that edge ask for NATO forces to move in for their protection. No longer just Estonia and Latvia, now NATO member countries Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania — all will have the Russian threat pressed up against them. NATO cannot stand back leaving those countries exposed. It will need to bring its forces to those eastern borders face-to-face with the Russians. The countries-wide buffer, no longer a buffer at all, will be just a pencil line on the map, sending the chance of war breaking out to soar. This will be the new permanent status in Europe for at least as long as Putin stays in power.

How long will that be? He has placed the head of the foreign unit of the FSB, formerly the KGB, and his deputy on house arrest for failing to foresee the strength of Ukrainian resistance. That could well be because they couldn’t risk telling Putin what he didn’t want to hear. A video clip of Putin berating one of his deputies shows what life must be like for the siloviki — Putin’s close administrators and advisers. Removal and possibly worse must cause others among them to wonder whether they’ll be next for defenestration. For self-preservation might they or the military decide to take action? buying time with iran

Iran was believed to be a year away from producing enough enriched uranium to make a bomb when the accord with seven nations was signed in 2015. But a campaign promise of Donald Trump’s was to get rid of “one of the worst negotiated deals of any kind that I have ever seen”. He thought it not stringent enough for its returning Iran’s embargoed money and failing to halt Iran’s missile development. It was an armchair assumption among those on the right that the U.S. could simply dictate terms to an Iran that after close to two years of negotiations simply would not yield. Trump withdrew the U.S from the accord in 2018, leaving in place no deal at all, only a promise he would negotiate a much better one. But across his four years as president he did nothing. He imposed sanctions and a “maximum pressure” campaign, but that left Iran free to develop more sophisticated centrifuges and set them spinning again.

The Biden administration is working to restore the 2015 agreement but now faces an Iran that is capable of producing enough weapons grade uranium to produce a bomb in a matter of weeks. The White House, faced with an array of other adversaries, would at least buy time with an admittedly diminished agreement of not having to deal with the Iran threat for a number of years. Or so it hopes. Iran is refusing to extend inspection rights to the International Atomic Energy Agency at certain of its facilities.

As with the original accord, Iran would be required to degrade or ship out of the country its 2 1/2 tons of enriched uranium, mothball its advanced centrifuges, and limit the purity of what uranium stocks it retains, ostensibly for medical uses, to a fraction of the level its assumed weapons program achieved.

In return the consortium would eliminate almost all sanctions. But the Kremlin has come up with a new demand, a guarantee that sanctions against Russia, a signatory of the accord, will not impede Russia’s “full trade, economic and investment cooperation and military-technical cooperation” with Iran. And a group of 33 Republican senators has warned the White House of opposition if Congress isn’t allowed a full review of whatever agreement is reached. Congressional involvement would spell the end of any deal. north korea rattles its sabers

North Korea has begun testing a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Launches in late February and early March were followed by a third just days ago that exploded shortly after liftoff over the capital city of Pyongyang. No reports or video of damage to the city or loss of life have escaped the tightly sealed country. North Korean followers think the missiles may have been of the sort that can be outfitted with a maneuverable or hypersonic warhead capable of eluding anti-missile defenses in California and Alaska.

Received wisdom says that North Korea is ramping up its tests because Washington has chosen to ignore leader Kim Jong-un, who seeks to have sanctions lifted. The pandemic, legislative social programs, and now Russia have proved distracting for President Biden. There have been no negotiations in over two years.

But the hermit kingdom’s behavior suggests that it will not be assuaged by a return to the exchange of “beautiful” letters that so pleased President Trump, who met three times with Mr. Kim with no result and ended with Trump threatening in September of 2017 to “totally destroy North Korea” and with Kim calling Trump’s behavior “mentally deranged”.

A voluntary moratorium against nuclear and intercontinental missile testing has been in force since November 2017, when what North Korea said was a hydrogen bomb produced a blast so powerful that it caused an earthquake. Mr. Kim is now considering “restarting all temporarily suspended activities”.

Pyongyang is building a major facility for ICBMs just 15 miles from the China border, out of reach of South Korea’s jets and a seeming deterrent to any attacker who might not want to risk angering the behemoth to the north. Facilities are built mostly underground or in caves to avoid detection and harden defenses. U.S. and South Korean officials estimate that there are 6,000 to 8,000 underground facilities, their locations unknowable short of a ground invasion. The mobility of trains mounted with nuclear missiles emerging from tunnels adds difficulty to targeting.

Mr. Kim’s total power and his country’s isolation from the world make him dangerous and unpredictable. Subduing North Korea, should it come to that, is a problem that defies solution. the china-russia connection

Five years ago presidential adviser and global strategist Zbigniew Brzezinski forewarned that “the most dangerous scenario” would be “a grand coalition of China and Russia…united not by ideology but by complementary grievances.” That has come about, and the grievance is against the West and most particularly the United States.

In the 1960s, Russia and China were enemies. A border war briefly broke out. They have forged an increasingly close bond in the decades since the break-up of the Soviet Union. They share a history of their countries’ mistreatment and join in the common purpose of diminishing America’s power and influence around the world. While still not quite a formal alliance, Xi Jinping told Vladimir Putin at a December video summit that “in its closeness and effectiveness, this relationship even exceeds an alliance”, according to a Kremlin aide privy to their exchange .

The two have formed a close personal friendship over the years. They have met 38 times. In 2019 Xi said Putin was his best friend. They issued a 5,000 word statement when they met at the opening ceremony of the recent Winter Olympic Games that declared their partnership had “no limits”. Western intelligence discerned that, so as not to upstage the games, Putin even delayed the Ukraine invasion. Chinese officials called that “pure fake news”. They scoffed at western intelligence warnings that Russia’s invasion was imminent, characterizing Washington, not Moscow, as the warmonger “manufacturing panic.”

China also has close ties with Ukraine. They were quick to recognize the new country shortly after the collapse of the USSR. China relies on Ukraine for major imports of wheat, corn, sunflower and grapeseed oil. With a fifth of the world’s population but only nine percent of its arable land, China in 2013 bought three million hectares — about 7.5 million acres the size of Belgium — 5% of Ukraine — for farming to bolster its food security.

Speaking to Putin three days before the invasion, Xi said all countries should “abandon a Cold War mentality”. Putin told him he would seek a negotiated resolution to the war, according to the Chinese government’s summary of the call. Yet Putin went ahead. There was no sign that Mr. Xi did anything to ward off the invasion. CIA chief William Burns said China’s own intelligence services didn’t appear to foresee Putin’s attack.

China at first went along, even avoiding the word “war” or “invasion”, only acknowledging a “conflict between Ukraine and Russia”. So they were deeply unsettled when they saw the stunning brutality of the Russian assault, calling for diplomacy and even expressing grief over civilian casualties.

The Biden administration seeks to drive a wedge between China and Russia by calling on China to condemn its new best friend. China’s reaction after one such entreaty was to report the attempt to Putin. Mr. Xi must balance between not wanting to jeopardize China’s trade relations with the U.S. and its still bigger customer, Europe, while at the same time preserving the strategic partnership with Russia.

U.S. intelligence learned that Putin is asking China for weapons, clear confirmation that the invasion goes poorly. Washington has threatened sanctions against China should it help Russia destroy Ukraine. Xi must realize that, after China’s often expressed emphasis on the sanctity of national sovereignty, its reputation would take a serious hit for backing the theft of a country — and by an invader that commits war crimes. The question is whether China is behind the scenes telling Putin he should back away, or whether Xi has chosen to stay uninvolved as they did by, rather than siding with Russia, abstaining in a U.N. Security Council resolution that condemned the invasion. And China has so far abided by the sanctions the Biden administration has levied against Russia. Implications for Taiwan

What does China take away from watching Russia struggle to take Ukraine? Taiwan is militarily a very different undertaking. An island makes for a more difficult invasion by amphibious landings and parachute drops after naval and air bombardment, but ultimately a simpler conquest of a landmass about one-seventeenth the size of Ukraine and a population half as many. Does the observed success of a fierce resistance cause Beijing to hold off, to prepare more deeply, especially for urban combat? Or, with the West newly preoccupied by NATO and Putin’s threats, and the U.S. stretched thin by having to operate in two theaters thousands of miles apart, does Beijing view this as an opportune moment to strike?

As described above, China recognizes Ukraine as a sovereign country but considers Taiwan as integral to China and not an independent country, and therefore does not consider invading Taiwan as violating its respect of national sovereignty. But Xi Jinping surely now sees that the world will not view it that way. If he held any doubts that China will be viewed as an international pariah when he invades the island, those doubts are gone.

acted as a buffer to keep Russia and NATO countries apart. Only Estonia and Latvia border on Russia if one doesn’t count Lithuania’s southwestern contact with Kaliningrad, a sliver of Russia separated from the mainland.

The NATO countries are in gray. Off the edge: The U.S., Canada, and Iceland.