Iran: Edging Nearer the Brink of War

It was one of his campaign promises — to get rid of “one of the worst negotiated deals of any kind that I have ever seen” — not that his base had ever asked for it. Itching to end the deal that put Iran’s nuclear development on hold, after acquiescing to its continuance in two mandated quarterly reviews, President Trump in October 2017 decertified the inspection reports, setting in motion the abrogation of an agreement that had taken almost two years to negotiate.

His national security team had strongly recommended that he keep the U.S. in the accord. In a statement that September, over 80 disarmament experts urged him to honor the U.S. pledge, calling the agreement a “net plus for international nuclear nonproliferation”. That the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which conducts non-proliferation nuclear inspections on site in Iran, had all along reported that Iran was in compliance with the terms of the pact was of no moment to the president. Neither had he concern for the five nations — Britain, France, Germany, Russia, China — who were allies with the U.S. in the deal and wanted, then and now, to preserve it. U.N. ambassador at the time Nikki Haley said at the United Nations, “This is about U.S. national security. This is not about European security. This is not about anyone else”, which left the five nations that alongside us laboriously worked out the Iran accord stunned.

Shortly after backing out of the deal, Trump reimposed the sanctions that had been dropped as part of the moratorium, and adopted a program of “maximum pressure”. The European allies, already cutting business deals with and selling goods to Iran, had no appetite to jettison the new opportunity that the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) had afforded them. As a riposte to Trump, Germany, France, and the U.K. scrambled to keep the accord alive, setting up a framework named Instex to skirt the sanctions with a barter trading scheme that does not use the dollar nor need the international funds transfer system. It just began operations in June with Russia showing interest. All the while, to encourage the Europeans, Iran stayed in compliance, as verified by the IAEA.

In May, Trump withdrew waivers that had allowed those and other nations to continue doing business with Iran without the risk of being sanctioned. So we’ve seen this White House ally with Israel, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates against Iran, and turn its back on former European allies. lashing out

The Iranian economy has been hard hit by the president’s maximum pressure which the Iranian rulers call “economic warfare”. Since his administration reinstated sanctions last year, Iran’s oil exports of 2.5 million barrels a day before the sanctions have fallen by more than half. The White House objective is to drive oil exports to zero. The Iranian currency, the rial, has lost more than 60% of its value against the dollar in the past year. The Iranian economy contracted by 4% in 2018 and is expected to contract by another 6% this year. The broken economy has caused Iran to retaliate. Six tankers have been hit, flagged by a number of nations, and a $130 million U.S. Global Hawk drone was brought down by a surface-to-air missile launched from the Iranian coast along the gulf of Oman. A British warship had to scatter three Iranian boats trying to block a U.K.-bound tanker from passing through the strait. The U.S. shot down a small Iranian drone that had come within a thousand yards of the USS Boxer, and now the Iranians have commandeered a British tanker, after having towed off another belonging to the United Arab Emirates.

Iran is pressing the European coalition to move faster on its trade plan, showing what could happen to their oil supplies and the attacks say as well that if Iran’s exports are halted by U.S. sanctions, oil exports of the Saudis and Gulf Arabs can expect the same. After the downing of the U.S. drone, a counterattack by the U.S. was called off by President Trump with only minutes to spare out of the his concern for loss of life compared to the loss of an unmanned aircraft. “I find it hard to believe it was intentional, if you want to know the truth”, Trump said. “I think that it could have been somebody who was loose and stupid that did it”. He is certainly the wiser by now. He instead struck back with further sanctions in late June, this time against the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei himself and the lucrative offices he commands.

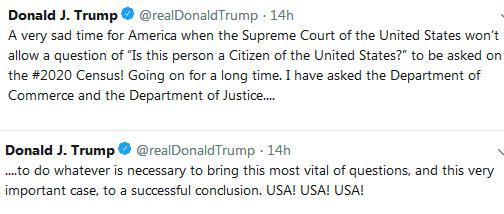

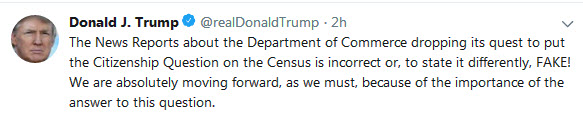

The president is reported as not wanting war — another Middle Eastern war could doom his re-election — but he has put himself right at its edge by his increasingly aggressive actions aimed at destroying the economy of a country of 80 million. breaking out

In June, IAEA inspectors warned that Iran was boosting production of nuclear fuel. On July 1 it was reported that their stockpile of raw uranium had exceeded the cap permitted by the deal. A few days later, President Hassan Rouhani, claiming Iran has the right to do so under the agreement if any of the parties breached, said they would enrich uranium beyond the 3.67% allowed and in “any amount that we want”, the first step toward a nuclear bomb. The JCPOA doesn’t rein in Iran’s missile testing, or centrifuge research, and doesn’t curtail their trouble-making around the Middle East, from Syria to Yemen to Iraq. It is an arms control agreement, its only objective. It may not cover everything, but it stopped Iran when on the verge of making an assumed nuclear weapon in 2015. But the president considers himself an expert: “I’ve studied the issue in great detail. I would say, actually, greater by far than anybody else. Believe me. Oh, believe me”. More, he therefore thinks, than even John Kerry who negotiated the deal over almost two years. “If you look at the deal that Biden and President Obama signed”, Trump averred, Iran “would have access, free access, to nuclear weapons in just a very short period of time”. He has made that statement repeatedly. The accord halted Iran’s nuclear development for 10 to 15 years dating from its 2015 signing. Cancelling the agreement has caused that short time to be right now, as we see Iran resume uranium enrichment, so Trump maintaining that reversion to no agreement at all makes less than no sense. It is legitimate to think the voiding of so important an agreement shows Trump’s willingness to damage America’s national security only for the purpose of exacting vengeance on Barach Obama for being the nation’s first black president, yet another act by Trump in his mania to destroy every accomplishment of Obama’s presidency. it didn’t have to come to this

Trita Parsi is president of the Iranian-American Council. He says that after the U.S. overran Iraq in 2003, the Iranians sent the U.S. a letter offering negotiations on almost all issues of contention between the two countries. Iran would agree to stop support of Islamic jihad and Hamas, and offer full transparency of its nuclear program. But in its triumphalist mood, the Bush Administration and its neoconservative coterie would go one better. They aspired to regime change in Iran. That had worked so well in Iraq. Uranium is enriched in spinning centrifuges. The George W. Bush administration decreed that Iran could not have any enrichment at all — “not one centrifuge spins”, was the edict of the State Department’s top proliferation official. Bush’s administration refused to negotiate unless all Iran’s centrifuges stopped spinning. So the few hundred working in 2003 expanded to thousands by the time Obama took over.

It happened again with Obama. He asked Brazil to see if it could resurrect a deal with Iran that had been proposed in 2008 and 2009. We had offered to take Iran’s lower enriched uranium and transfer it to Russia, which would produce fuel pads for creating Iran’s medical isotopes, the country’s avowed reason for enriching. Brazil succeeded, but at the same time that the U.N. Security Council voted sanctions against Iran. The Obama Administration opted for sanctions instead of the deal. So the centrifuge count swelled to 19,000. breakout”

“In March of 2012, the United States and five other nations accepted a January offer by Iran to enter into talks, with Iran willing to discuss its uranium enrichment program for the first time. Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu believed that talks were just “running the clock”, a delaying tactic while Iran worked on a bomb. He argued that Iran should suspend uranium enrichment as a precondition to any talks. The Obama White House said that would end the talks before they began.

With 19,000 centrifuges spinning and an enriched stockpile already in hand, Iran could create enough enriched uranium for a single bomb in a mere 2-3 months — the so-called “breakout time”. The U.S. and negotiating partners were entirely focused on lengthening the breakout time. They set their sights on assuring that if an accord could be hammered out but Iran someday chose to break it, at least a year would be needed before breakout could be reached.

An interim accord was struck by January 2014 that gave Iran modest sanctions relief in exchange for them suspending the most sensitive aspects of their nuclear program. Negotiations went on for a scheduled six months. Talks were extended another four months to late November. That date came and went with little progress and another extension of the status quo was agreed to, this one to the end of June of 2015. After last minute attempts at re-trading by the Ayatollah, the document was signed July 15th 2015.

All of which is to point out that the negotiations were a protracted process, with Iran toughing it out with its “resistance economy”. Yet all Republicans in the Senate, joined by 10 Democrats, pressed for a tougher set of sanctions to bring Iran to heel and end what they considered to be stalling while Iran advanced weapon development in secret locations. A prevalent view was that Obama, too, was stalling so as to avoid military action against Iran’s nuclear advances so as to hand the problem to the next president.

Rather than everyone stalling, the negotiators were in a breakneck hurry. There was worry that the existing sanctions would collapse, ending any Iranian need for the nascent deal. More than the six negotiating nations had adhered to the sanctions, but countries such as Japan, South Korea and India were restive about indefinitely injuring their economies. Another layer of sanctions coming out of Congress risked that Iran, having reached breakout capability, would simply go for the bomb. a better deal

Netanyahu — “a prime minister who’s never seen a war he didn’t want our country to fight”, said California Rep. Jared Huffman — lobbied hard to undermine Obama. He had even gone behind Obama’s back by inviting himself to speak before a joint session of Congress, which gave him the customary standing ovation in appreciation of campaign funding by the Israel lobby. “I think a better deal is possible”, Netanyahu said to everyone who would listen. Tougher sanctions would force “Iran to choose between lifting the sanctions and rolling back, truly rolling back, their nuclear capability”. The Obama administration, knowing the intransigence of the Iranian negotiators, assumed the opposite, that if more sanctions were added, Iran would build its bomb. the actual deal

When negotiations began, the hope was to eliminate the centrifuges altogether and ship the enriched uranium out of the country. But the Iranians tested the U.S. and its partners’ eagerness to strike a deal by just saying ‘no’ to one after another demand. “As soon as we got into the real negotiations with them, we understood that any final deal was going to involve some domestic enrichment capability,” a senior U.S. official said. Only 5,060 less efficient first generation machines could stay on line, restricted for 15 years to enriching no higher than 3.67% in U-235 isotope content, a level suitable for power plants and medical isotopes, but nowhere near 20% level needed for a nuclear bomb. Iran decreed that the rest of the 19,000 centrifuges were not to be destroyed, only mothballed, or no deal.

They insisted the enriched uranium be diluted rather than shipped out of the country. Creation of a heavy water reactor meant to extract plutonium was halted. The Ayatollah ruled out inspection of military bases. “It must absolutely not be allowed for them to infiltrate into the country’s defense and security domain”, he said. That left the Parchin base, suspected of conducting research on nuclear weapons, off limits.

Nowhere in the talks were restrictions on Iran’s ballistic missile program considered. The Obama administration agreed not to bring it up despite no country lacking an atomic warhead ever having been interested in developing ICBMs. Rouhani tweeted “In #Geneva agreement world powers surrendered to Iranian nation’s will”.

The defects of the final agreement were real and worrisome, but the notion that a better deal could have been struck took no notice of how long the negotiations had taken with repeated deadline extensions as the parties fought over final terms and language. Detractors wanted return of hostages, renouncement of threats to Israel, prohibition of missile development, promises to make nice in the region. “Does this deal resolve all other threats Iran poses to its neighbors in the world? No”, said Obama. “Does it do more than anyone has done before to make sure that Iran does not obtain a nuclear weapon? Yes. And that was our top priority from the start.” Those opposed were astonished at a deal that would allow Iran to emerge a decade later with the full capacity to create a nuclear bomb, never mind that without the deal Iran could produce enough material for a bomb right then and there in three months. “They were months away from it in 2013”, said Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va) in 2015 when the deal was before Congress. “Could you imagine a point at year 15 or 25 where they might do something bad? Yes, you could …but remember that we were at that point two years ago”, before the interim accord froze Iran’s activities so that talks could proceed. The deal bought time. How to explain alarm for the future greater than alarm for the immediate present? a tough road ahead

The maximum pressure campaign has served to breed solidarity and embolden the hard-liners in Iran. Our fond notion that the people of Iran long for relations with the West has turned to anger with inflation crossing 50%. The urban public may have moved away from the religious theme of the revolution, but they have now turned to the nationalism of the Revolutionary Guard, angered at classification by the U.S. as a terrorist organization. They see the guard as their best defense against the United States. An Iranian poll, if truthful, says 72% of the people do not think Iran should negotiate with the West because it is untrustworthy.

There is no hint of a willingness by Iran to negotiate a replacement deal, and Trump has never spelled out what he seeks other than the usual “better deal”. He, with Mike Pompeo and John Bolton at his side, really should review the history outlined above of how limited were the concessions that took 20 months for six nations to wrest from Iran before they assume forging a much better deal with Iran will be simple. And yet there was Pompeo at the Heritage Foundation in May of last year laying out 12 demands that Iran must accede to. Among them:

It reads like unconditional surrender for a war not yet fought.

![]() Ending enrichment of uranium—a ban imposed on no other country. The non-proliferation treaty confers an “inalienable right” to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.

Ending enrichment of uranium—a ban imposed on no other country. The non-proliferation treaty confers an “inalienable right” to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.

![]() Giving international inspectors “unqualified access” to “all sites throughout” Iran—a license for espionage that no country would accept.

Giving international inspectors “unqualified access” to “all sites throughout” Iran—a license for espionage that no country would accept.

![]() Halting tests and development of ballistic and cruise missiles.

Halting tests and development of ballistic and cruise missiles.

![]() Ending support for Syria, Hezbollah, the Houthis in Yemen.

Ending support for Syria, Hezbollah, the Houthis in Yemen.

![]() Disarming its militias in Iraq.

Disarming its militias in Iraq.

![]() Ceasing all threats against Israel.

Ceasing all threats against Israel.