With Ebola Raging in Africa, Why Risk Bringing It Here?

Oct 24 2014Incredibly, even the Ebola scare became political no sooner than it arrived in Dallas. Republicans began arguing for travel bans, Democrats for open borders,

the President hesitant.

"I don't have a philosophical objection necessarily to a travel ban if that is the thing that will keep the American people safe", said Obama, but experts have told him that a travel ban is less effective than the measures "we are currently instituting": educating hospital personnel across the country and temperature checks at five airports through which all travelers from the three afflicted West African nations must now pass.

That didn't ensnare a doctor working with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) who had no symptoms when he returned from West Africa but who checked himself into New York's Bellevue Hospital days later when he ran a fever and was diagnosed with Ebola. When a second MSF healthcare worker named Kaci Hickox landed at Kennedy and, agitated by being detained for six hours showed a slightly elevated temperature, three governors — Chris Christie of New Jersey, Andrew Cuomo of New York and Pat Quinn of Illinois — made the colossal blunder of declaring that all returning personnel from the region who had had any contact with Ebola patients would be quarantined for 21 days, a decision made with no contact with the White House or federal health officials. Christie jailed Hickox in a tent at a Newark hospital with a port-a-potty, no television, no books. Her captors even wanted to take away her cell phone.

The medical community reacted immediately against an extraordinarily ill-considered policy that was guaranteed to end the flow of medical volunteers to fight contagion in Africa if they face mandatory quarantine every time they return for a break. The governors walked back their edict and Hickox was released to go home to Maine. Christie denied he had reversed his policy, as if we had imagined him announcing the 21-day plan, and tried to lie his way out of his debacle saying "she was running a high fever and was symptomatic" which was not the case. Hickox is suing.

separationIt will seem that we are now arguing against ourselves when we now say that fruit bats cannot cross the Atlantic to bring us Ebola, so why not impose travel restrictions to severely limit the disease from coming into the U.S. in the first place. There has been panicky reaction to the specter of Ebola from the public as well as from governors — Oklahoma kids pointlessly kept home from school because a few had been on that cruise ship where they had no contact with a self-quarantined Dallas lab technician who showed no symptoms, for example — but it is not a panicky response to ask why leave our doors open to everyone from the afflicted countries so we can treat Ebola here, when public health officials say it is essential that we take every measure to defeat the epidemic there?

disagreementsThe arguments against a travel ban suffer from confusion. It would make the epidemic worse, is said continuously but unconvincingly. Wouldn't it impede getting needed aid into the afflicted countries? Well no, because a ban would only prevent people from coming out. How would medical personnel, crucially needed in those countries, come and go if there were a travel ban? They would be exempted from the ban, of course. The free movement of medical personnel, who need of course to be monitored, who of course need to be quarantined if they then present symptoms, is the obvious exception if we are to enlist them in the fight.

But the Center for Disease Control's (CDC) director Thomas Frieden and others have said the ban won't work because people will simply detour through other countries. Even if that were an effective method for the few to defeat the system, the many — currently upwards of 150 arriving daily at U.S. airports from the stricken countries — would be blocked.

It is vacuous even to suggest that end-runs would be a problem. No matter what route people take they are identified by their passports, as well as passport stamps or customs' online data that indicate where they have just been. And an outright ban is the wrong word. The U.S. can simply closely restrict the issuance of visas until the disease is defeated.

Another argument is the damage it will do to the frail economies of the West African countries.

The danger is that if other nations followed an American ban with bans of their own, economies in West Africa would be crippled. That could only reduce the ability of those nations to fight the epidemic, and make it even more likely the disease would spread through porous borders to other African nations and beyond.

says a New York Times editorial. But no one is waiting to see what America does; 14 African nations have banned residents of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea from entering their countries, and 14 other African countries have enacted travel restrictions.

The economies of the stricken countries will be wrecked anyway. "Schools have shut down, elections have been postponed, mining and logging companies have withdrawn, farmers have abandoned their fields", says this Times piece from two days earlier. There are 10 times fewer burial teams than are needed for lack of the willing, and there are threats of strikes by health workers and gravediggers in Sierra Leone. Helene Cooper, a Times correspondent and native of Liberia who was recently there, said on Andrea Mitchell's cable news show that while there is progress — increased education, signs in the street advising people, public chlorine washes — there is "no question that Ebola has hit Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea very hard...so many businesses have now pulled out of Liberia, so much investment has started to come out...so when you see the flight of capital and resources, that's a big deal".

Tragic, but it renders inconsequential the harm a travel "ban" would do to their economies. And worse is to come. The World Health Organization predicts 10,000 cases a week of this devastating disease by December. Make that up to 1.4 million West Africans that could be infected by the end of January, according to the CDC's estimates. Economic restoration of these countries will have to wait until the contagion is overcome.

pacificationThose geometrically progressing numbers should tell us that in the coming months there will be a steadily increasing likelihood that someone among the 150-a-day arriving passengers will be carrying the virus.

Yet, Ebola is an "unlikely candidate for epidemic status" says an editorial at BloombergBusinessweek because it can only be contracted by contact between the bodily fluids of the ill and our soft tissues, such as eyes and mouth. Why, measles is easier to catch, we're reminded.

Compared to this blithe reassurance, the reality of top to bottom hazmat suits and the gutting of all the seats and carpeting of the aircraft that took one of the Dallas nurses to Cleveland makes for a glaring contradiction. The edit makes no mention that the measles fatality rate before vaccines was 0.0129%; the fatality rate for Ebola is from 50% to 90%.

A travel ban is a terrible idea, the editorial continues, because it could disrupt trade. And besides, "people want to travel to see family and friends, visit places, work, or invest. We think all that is worth the price of somewhat increased risks of illness."

virulenceTexas Congressman and doctor, Michael Burgess, gave us a sense of how wishful were those musings on Andrea Mitchell's news program:

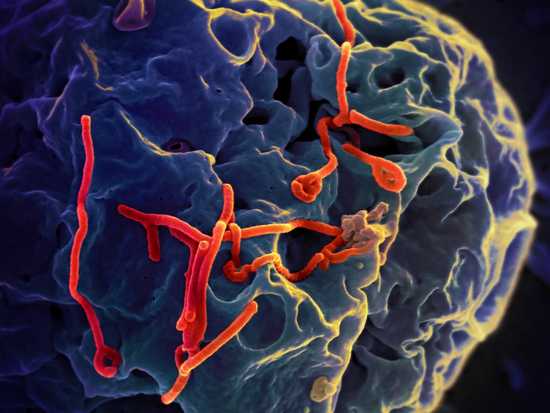

"The CDC was telling us to prepare for this virus the same way we might prepare to take care of a patient with hepatitis A. [Ebola] is different. The viral load, the disease burden in a patient who is near the end of the struggle with this disease, it's unlike anything anyone has ever seen before. The virus may not be airborne but it can be everywhere in the room because there's just so darn much of it in a patient who is unfortunately at the end of the clinical course."

If that is somehow not persuasive,

A patient in the throes of Ebola can have 10 billion viral particles in a fifth of a teaspoon of blood — far more than the 50,000 to 100,000 particles seen in an untreated patient with the AIDS virus. Even the skin of an Ebola patient can be crawling with the virus.

That was Dr. Bruce Ribner, a physician involved in the care of Ebola patients treated at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. This is what the President, who has the authority to restrict travel under the 2005 Pandemic Plan, is potentially allowing to enter the United States.

ebola exceptionalism?The three besieged countries in West Africa have weak health infrastructures that quickly were overtaken by the disease, whereas the United States has one of the best health systems in the world, goes the argument. True enough, when there are only a few cases that need to be isolated and controlled. But with only four facilities equipped to handle highly infectious diseases — Emory alongside CDC in Atlanta, NIH in Bethesda, and hospitals in Omaha and Missoula — and the expectation that future cases are best transferred to these sites, we are less prepared than claimed should cases suddenly multiply and these facilities become overwhelmed. The fallback is presumed to be the larger regional hospitals to which patients would be transferred. But that brings up the question of how transferred?

The only aircraft in the U.S. that are adapted for sealing off the cargo of an infectious patient are two Gulfstreams owned by government contractor Phoenix Air. A third is being outfitted. A VP of Phoenix cautions in a Times article that

Branden Camp/European Pressphoto Agency

transport is “the easy part…It is a nasty, nasty disease and ultracontagious”. "Decontaminating an aircraft once the patient is dropped off is the hard part…an elaborate 24-hour process of treatment with chemicals and the removal and burning of seatbelts, lights and anything else that might have come into contact with the sick passenger". An added concern: there may be a problem of finding pilots willing to fly Ebola patients, as is occurring with a French company comparable to Phoenix. They will fly only "dry patients", patients who are not bleeding, vomiting and are free of diarrhea. The general director of that company says he knows only two pilots in all of Europe who will fly Ebola evacuation missions.

Why bring this up? To make the point that in a general outbreak, there will be too many patients to transfer elsewhere. They will need to be treated at local hospitals wherever the disease turns up. Note some of the local reactions at Emory in Atlanta where only three medical personnel brought in from West Africa were treated. The county threatened to cut the sewer system off if the hospital flushed medical waste, trash companies insisted that all takeaway be sterilized, couriers would not drive blood samples to testing labs, and the staff could not even get pizza outfits to deliver.

If in this day of increasing threat from drug-defying pathogens — such as SARS, MRSA, KPC — if we do not prepare with thorough training and upgrading of facilities to gain the confidence of medical personnel, a wildfire of contagion could lead to a break in their willingness to serve.

All of which argues that the deliberate gamble of an open door policy is unwise. Contemplating the possibility of outbreak and what needs to be done to prepare is not panic; it is precaution. Rham Emanuel's nostrum of "never let a serious crisis go to waste" is not the right prescription in this case. With Ebola we must not, as usual, find ourselves deciding after a calamity to do a better job. We cannot always stop a disease at the border but we can slow it down in order to give this country the opportunity to organize against a medical emergency.

Please subscribe if you haven't, or post a comment below about this article, or

click here to go to our front page.