Cracks Develop in the Iran Deal’s Framework

And only a couple of months to patch them Apr 18 2015

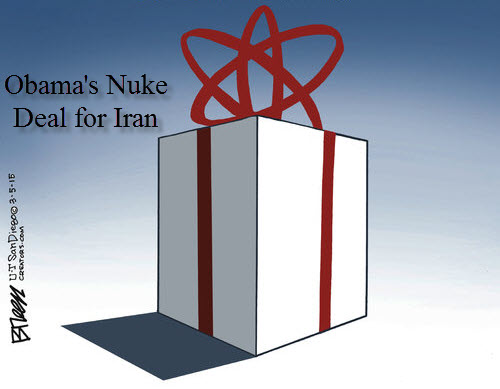

One view of the talks

Steve Breen, UT San Diego

The ink was hardly dry on the term sheet rushed out by the U.S. before it began to smear. Called a "framework, it was immediately disavowed by Iran's negotiators who felt they'd been framed. That the list was immediately released to the media was clearly an attempt to hold the Iranian negotiators to their word.

The Iranian public was joyous at the prospect of sanctions removal, but Iran's President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif had hoped to avoid details spelled out in public that would give ammunition to hard-line critics that think their negotiators gave away too much. They already faced the difficult job of selling the deal to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has the ultimate say.

That didn't go well. A week later, the Ayatollah denounced the agreement on state television. “Everything done so far neither guarantees an agreement in principle nor its contents, nor does it guarantee that the negotiations will continue to the end”, he reminded all parties to the tenuous seven-nation accord while calling the U.S. "devilish" and "backstabbers".

Zarif and Rouhani seem genuinely intent on sealing a deal and taking some steps toward normalizing relations with the West after 35 years of hostility with America. The CIA's intelligence, revealed by Director John Brennan speaking at Harvard a week after the terms were announced, says that President Rouhani told the Ayatollah that the country's leadership could be in peril and its economy, having felt the bite of six years of sanctions, is "destined to go down" if an understanding cannot be reached.

That may be why President Obama confidently said the Ayatollah is only playing to the public to protect his regime's standing in their eyes. “Even a guy with the title supreme leader has to be concerned about his own constituencies,” said Obama at the Latin American summit in Panama, which, given Khamenei's vitriol, seemed wishful in the extreme. Having firmly demanded that all sanctions be lifted immediately as a condition of signing the deal, and that inspectors will not be allowed on military bases, how does Obama imagine the Ayatollah will explain to those constituencies three months from now that it was only bluster?

It seems that the agreement announced on April 3rd, heralded a bit too hastily in a New York Times editorial as "a significant achievement that makes it more likely Iran will never be a nuclear threat", has turned into more of a list of disagreements.

sanctionsThe Ayatollah Khamenei insists on immediate sanction relief the moment final documents are signed, signaling that he will not agree to the terms negotiated. The framework says sanctions will be lifted if Iran "verifiably abides by its commitments" and President Obama has repeatedly insisted on relieving sanctions “in a phased way”. He was not surprised that Khamenei and his negotiators are characterizing the deal “in a way that protects their political position.” He reiterated his own demand with, “If that is his understanding and his position in ways that can’t be squared with our concern … then we’re not going to get a deal.”

There is no timetable linking sanctions to each of steps Iran is required to take, and obtaining agreement to a schedule should prove dicey in the negotiations to come. If the U.S. and partners were to capitulate to the Ayatollah, among other blessings showered upon Iran would be the release of $100 billion in blocked funds before Iran had honored any of its obligations.

What is called the "architecture" of restricted imports will be kept in place to "allow for the snap-back of sanctions in the event of significant non-performance" in the words of the term sheet. But there is confusion. A State Department representative spoke of "suspension" as the first step. "It’s suspension and then later termination to ensure that Iran has abided by its commitment.”

Once undone, sanction reinstatement will not be simple, and with commercial relations profitably reestablished, the question is whether the negotiating partners — particularly Russia and China — can be counted on to re-commit?

centrifuges & enrichmentCentrifuges spin to enrich uranium. The Bush administration refused to negotiate unless all Iran's centrifuges stopped spinning. So the few hundred working in 2003 had expanded to thousands by the time Obama took over and the count has since swelled to 19,000.

The hope in the current negotiations was to eliminate the centrifuges altogether, but Iran decreed that none are to be destroyed. “As soon as we got into the real negotiations with them, we understood that any final deal was going to involve some domestic enrichment capability,” a senior U.S. official said, so the Obama administration yielded, allowing Iran to keep 5,060 less efficient first generation machines — at the Natanz facility only, restricted for 15 years to enriching no higher than 3.67% in U-235 isotope content, a level suitable for power plants but nowhere near 20% level needed for a nuclear bomb. The rest of the centrifuges are only to be idled or mothballed.

At Fordo, the secret facility deep within a mountain and discovered during Obama's first year in office, there is to be no fissile material nor uranium enrichment for 15 years. The plant is to be used to produce medical isotopes.

But there is no restriction at the Fordo site about what type of centrifuge can be retained there, and while inspectors may see to it that they do no enrichment, in the event of a breakdown in the agreement, they “could be rapidly repurposed for enriching uranium under a breakout scenario” that could produce the fuel for a bomb in as little as three months". That's the belief of R. Scott Kemp, a centrifuge expert at M.I.T.

anywhere, anytimeThe framework of "parameters" released by the Obama administration covers "anywhere" quite thoroughly but there is no mention of "anytime". It says that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is to have "regular access to all of Iran's nuclear facilities" and "suspicious sites of allegations or a covert enrichment facility, centrifuge production facility, or yellowcake production facility anywhere in the country" as well as monitoring of the industry's supply chain. What it does not promise is the "anytime" unannounced access of surprise inspections. Will Iran insist on by-appointment-only and long advanced notice

In his television appearance the Ayatollah ruled out military bases. “It must absolutely not be allowed for them to infiltrate into the country’s defense and security domain under the pretext of inspections,” he said. Why that is important to the U.S. and partners is because at least one major military site, Parchin, is suspected of conducting research on nuclear weapons. The IAEA has repeatedly been denied access by Tehran.

And if Iran blocks access or is suspected of cheating on any of the requirements of the agreement? Secretary of State John Kerry said on the PBS NewsHour,"We’re going to have a very robust inspection system", but the framework says only that “a dispute resolution process will be specified” by which any of the signatories can “seek to resolve disagreements”. Asked about military bases, Kerry evaded.

enriched stockThe stockpile of already enriched uranium — listed as 10,000 kilos in the Framework — was to have been shipped out of the country, presumably to Russia, presumably to be converted to rods for use in power plants. But just days before the end-March deadline, Iran refused and the Framework shows that the parties acceded.

Stocks are to be "reduced" to 300 kilos in some unspecified away that does not account for what is to become of the remaining 9,700 kilos, with the small remainder diluted and held to the 3.67% limit for 15 years.

There is an ominous portent to the maneuver, as if Iran is poised for a breakdown in the agreement. Was there perhaps anguish over the fact that once out of the country, the stock would be irretrievable? Kept at home, Tehran would not have to start over.

past workIn 2011 the IAEA put forth a report that listed a dozen concerns it has about Iran’s past nuclear work that could have military dimensions. Tehran has so far partially answered only one. It is difficult to be certain that Iran would need a year after breakout to produce a nuclear weapon if we do not know how far they have already progressed. Olli Heinonen, the former Deputy Director-General for Safeguards at the IAEA, makes the point: “You need to have that baseline [to] disclose past military-related nuclear activities. Iran is increasingly looking like it’s not going to do this. Is the U.S. prepared to accept that?" The Obama administration hasn't made clear what it will require, but John Kerry did in an interview with the NewsHour's Judy Woodruff. "No. They have to do it", that is, answer all the IAEA's questions. "It will be done. If there’s going to be a deal; it will be done… It will be part of a final agreement. It has to be". But there is no sign of progress in the Framework.

researchIran's insistence that it may continue with its research and development on advanced centrifuges was the subject of a "lengthy battle" with Iran the victor. One has to ask, why the obsession over centrifuges if no bomb is intended? Is nuclear blackmail part of this ayatollah's grand design for Iranian hegemony in the Middle East as we see it extend its reach, and is the acceptance of the framework only a temporary expedient to end the sanctions and rebuild the Iranian economy before resuming the grand plan? If not, why does Khamenei have a dream that he voiced his dream last summer of building 190,000 centrifuges?

Reuel Marc Gerecht, a former CIA analyst who is now a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, warns, “A reading of the supreme leader or of Hassan Rouhani in their own words ought to tell you that there is a near-zero chance that an accord will diminish the revolutionary, religious hostility that these two men, the revolutionary elite, have for the United States”.

closing the dealThat it has taken 19 months of negotiations to arrive at a robust list of demands, but not signed to by Iran, partly rebuffed by Iran's supreme ruler, and with details to be worked out in only three months (when it is usually th details that are the mostly hotly argued), says that arriving at Obama's hoped-for pact with Iran by the end of June is a precarious bet.

And we haven't yet mentioned Congress. It wants a say beyond the fact that it is up to them to rescind the sanctions because they are congressionally mandated. Engineered by Republican Senator and committee chair, Bob Corker (R-Tn), the Senate Foreign Relations Committee just voted 19-0 on a bill that would give the Senate 30 days to review any final deal, the President 12 days to veto any disapproval, and 10 days for Congress to override the veto.

But the bill itself should earn Obama's veto for attempting to take away his legislated power to waive the sanctions temporarily - flexibility that he will surely need for perhaps the most sensitive tripwire that could blow up the deal.

Further, this is only a committee vote. For Congress at large to now barnacle the pact with amendments to toughen the deal and then expect seven nations to give them even a moment's consideration after two years of painstaking work and argument is an absurdity.

Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu is expected in these few months to spur Congress to disrupt any deal with his pronouncement that "no deal is better than a bad deal", demagoguery that in fact makes no sense. The reality of the negotiations is that Iran, toughing it out with its "resistance economy", has been testing the U.S. and its partners' eagerness to strike a deal by just saying 'no' to one after another demands. A tougher deal short of war would mean another layer of sanctions and the risk that Iran, having an often mentioned breakout capability now standing at only two to three months, would simply go for the bomb. Any agreement that inhibits Iran's march toward nuclear weapon capability is obviously better than no agreement. Will Congress figure that out?

Please subscribe if you haven't, or post a comment below about this article, or

click here to go to our front page.

These Persians have always been tough negotiators. They’ve been at it for a few

thousand years. We are challenging them on their own ground. The odds for a final agreement that works? These are not good. Still, as long as everybody is busy negotiating, at least they aren’t out making trouble.