Have Republicans Finally Abandoned the Laffer Curve?

No way that candidate tax plans can pay for themselves Nov 4 2015About this time four years ago in the run-up to the 2012 elections, Bloomberg/BusinessWeek ran an article titled, "The GOP Heads Straight for the Laffer Curve", the notion that cutting

income taxes results in higher government revenues. Leaving money in the public pocket spurs investment, growth and higher taxable incomes that, despite reduced tax rates, throw off more income than the higher tax rates they replace and more than pay for themselves.

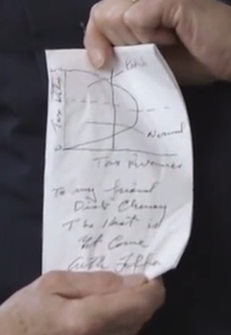

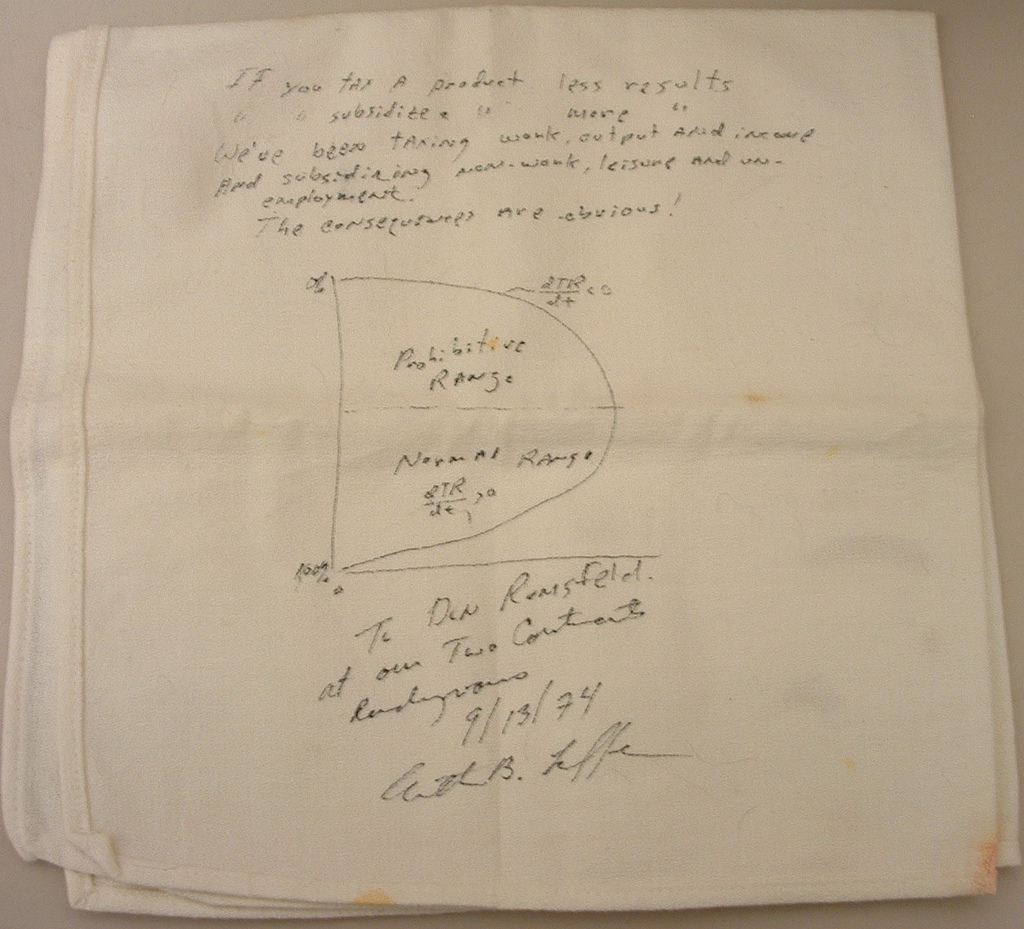

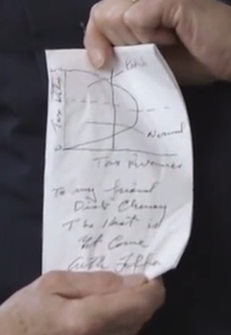

Lacking any conclusive proof that this is true, this brainstorm of economist Arthur Laffer has nonetheless become an unquestioned article of faith for Republicans, even though rejected by economists of all political persuasions. Laffer preaches economic gospel from his offices in Nashville and whom The New York Times dubbed "the Reagan era economist and godfather of supply-side economics". The experiment that Republicans wish to apply to nothing less than the entire budget and revenue streams of the United States was literally born on a cloth napkin over dinner at the Hotel Washington in DC in 1974. Laffer was demonstrating his idea at dinner with a couple of government types named Dick Cheney and Don Rumsfeld, well before the ascendancy of either of them to the vice presidency for one, and chief of staff and defense secretary for the other.

So why has this notion that Democrats consider voodoo proved so durable? Without it, without the ability to claim that tax cuts bring in more revenue, not less, how could conservatives make a case for cutting taxes while simultaneously railing against the $18 trillion-plus national debt that the cuts would aggravate still further?

But in this campaign, the Republican candidates seem to have all but given up on this counter-intuitive exercise in magical thinking. They are instead competing with each other with tax cuts so deep that they can no longer pretend they are not adding trillions of dollars to the national debt.

A companion cardinal principle is that higher taxes reduce the incentive to work. You can just about make this out in Laffer's notes on the napkin ("We've been taxing taxing work, output and employment...")

The original napkin, dedicated to Rumsfeld

"High tax rates stifle innovation, work, investment and American competitiveness", says Stephen Moore in the Weekly Standard", Bill Kristol's magazine. Cut taxes and people work harder, producing higher taxable income.

This is assuredly true in the extremes — at the 90% maximum tax rate of the Eisenhower years, top earners probably threw up their hands and said, why bother — but otherwise this smacks of standard economists' doctrine where if one line on the blackboard goes up, the other must come down, as if it were a Newtonian law of physics. This ignores the fact that we have no option other than to work to support ourselves and put our kids through college no matter whether tax rates rise or fall. Laffer seems to presume that we've been free to exercise discretion in whether or not to work hard in reaction to today's taxes rates, that in a kind of Pavlovian reaction, we will surge forward if taxes are cut with a burst of new-found energy and productivity, with the government making more money from our expanded effort.

An op-ed in the Wall Street Journal tells us, "A higher rate on the next dollar a worker earns discourages him from working more. The highest tax bracket is especially important as top earners produce the most and innovate the most". That questionable assertion is the rationale for cutting the tax rates for top earners, far and away the group that benefits the most from the reform proposals of all the candidates.

Jeb Bush would cut the top rate from 39.6% to 28%. He wants symbolically to match Reagan's 1981 cuts. So do Kasich and Christie . Trump would make the top rate 25%, as would Jindal. As a sort who probably haven't been near a form 1040 in years, all make a fetish of cutting the number of tax brackets from the current 7 to, usually, 3 — as if that's what make taxes complicated rather than the 74,000 page tax code that Carly Fiorina wants to cut to three pages.

Let's make it really simple with a single rate, say the others who have announced plans. They want a single "flat tax" rate for all: 20% for Santorum, 15% for Carson, 14.5% for Paul, 10% for Cruz. Huckabee would do away with income taxes altogether, substituting a 23% national sales tax. All would cut corporate rates from the current 35% to as little as 0% (Jindal).

It's easy to see that the Laffer Curve can't come to the rescue, and why none of the candidates is making much of an attempt to pretend that these steep tax cuts will lead to such growth that tax receipts will soar beyond the lost revenue of the cuts. Instead they are counting on a new gimmick in budget forecasting called "dynamic scoring" to somewhat ameliorate the runaway debt their plans produce. The argument is that if taxes are cut, growth will follow and it's only fair that forecasting should factor that in, even though there is nothing consistent in past experience to go on, and the amount of growth to plug in is whatever you hit on the dartboard.

So while the Tax Foundation says Jeb Bush's plan would produce a $3.6 added deficit over 10 years, he says that growth would back that down to $1.6 trillion. We don't see Santorum's true shortfall, because he cites an imagined net of $1.1 trillion "after increased growth and job creation" (and even that will be wiped clean with his cancelling Obamacare and its costs). Ted Cruz does the same, ducking the raw revenue loss of his 10% flat tax and assuming less than $1 trillion "with dynamic scoring" when, clearly, a universal tax rate so low would lead to government hemorrhaging. The only candidates not playing this game seem to be Jindal's, whose flat tax would result in a $9 trillion 10-year deficit — a 22% drop in government revenues — and Trump's plan which leads to a $10 trillion drop.

Even Marco Rubio, who went counter to the rest with a top tax rate of 35%, would run up a $4 trillion debt because of doing away with all taxes on capital gains and dividends and advancing a costly social program of child tax deductions.

As should be clear, the deeply reduced tax rates of the other candidates leaves the government with huge revenue losses so that the trillions can be transferred largely to their patrons in the top income class.

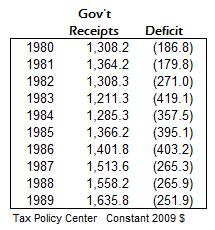

but it's doctrineThe candidates may not be able to make extravagant Laffer Curve claims, but the indoctrinated still carry on. Republicans cite what followed the Reagan tax cuts as incontrovertible proof that reduced taxes produce the growth that brings in higher tax receipts. It's a difficult case to make when the subject is the vast U.S. economy with so many other forces at play, but they need a mystical gospel to justify the tax cuts that attract votes. "When Reagan reduced the top marginal tax rate from 70 to 28 % in the 1980s, the Laffer Curve effect was indisputable. The economy exploded, tax revenues nearly doubled over the decade", says Stephen Moore.

"Doubled" is an astonishingly dishonest claim because Moore used dollars unadjusted for inflation so he could compare 1980's $517 billion to 1990's $1,032 billion. This table, properly adjusted for inflation, proves him to be a charlatan (fiscal 1989 included as policy overlapping from Reagan's last year; similarly, 1980 really belongs to Carter):

No surprise that revenue in fact fell for the first few years as a consequence of the tax cuts and to such a degree that the 1986 Tax Reform Act had to raise taxes because the government was in trouble, but Moore doesn't mention that.

Of Jeb Bush's "growth" plan The Wall Street Journal said in September, "The Reagan tax reform cut the top rate to 28% from 50% [sic]. That reform helped to sustain the 1980s economic boom and set the stage for growth through the 1990s". Thus does doctrine even claim that Reagan deserves the credit for Clinton's boom years.

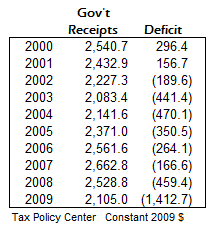

What about the Bush tax cuts? Are they used to prove the Laffer Curve? Revenue rose (see table) but, "For the last four years tax receipts have consistently come in below expectations...revenue remains far lower than anyone would have predicted before the tax cuts began", wrote

economist Paul Krugman in 2006. "In January 2001, before tax cuts were known, the budget office forecast $2.57 trillion in fiscal 2005. Even with the recent increase in receipts, the actual number will be at least $400 billion less.

What about now? Look at North Carolina, says Moore. In the 2012 election, Republicans took the governorship as well as control of the legislature. In 2013 they rapidly enacted tax cuts (and extreme voting right changes challenged by the Justice Department) that dropped the personal and corporate rates by a quarter. According to Moore, the state budget office says that, despite tax cuts, revenue increased by 6%, a Laffer triumph it would seem, but we've seen how Moore fudges data.

The state cut unemployment benefits to the lowest in the nation: from $535 weekly to $350 with no extensions beyond the minimum 20 weeks, the shortest in the country. Moore calls this "tough love" and says that owing to the peaceful, weekly Moral Monday demonstrations (this writer lives in North Carolina), "the state boiled over with rancorous political rallies". The question, though, is whether the $2.8 billion saved by these cuts are being counted as revenue improperly attributed to the Laffer theory, which is tied only to tax cuts, not budget cuts.

what's the matter with kansasWhich brings us to Kansas. Laffer himself was behind the current engineering of the recent Kansas's experience. Governor Brownback set out to slash taxes; growth would more than make up the nominal reduction in government revenue. "We'll see how it works", said Brownback. "We'll have a real live experiment". The Republican legislature approved the various tax cuts in 2012 and 2013.

It did not go well. The radical tax cuts, with cuts in public services and a tax increase focused on lower income people, led to a $400 million budget, which in led this year to an embarrassing reversal, the largest tax hikes in Kansas history to cover the shortfall, passed by the legislature at 4AM one morning in May. "I think it's clear that the tax cuts were promoted as having these quick and strongly positive results, and they haven't", says Ramesh Ponnuru, a senior editor at National Review.

Proof of its efficacy lacking and derided by economists though it be, the perpetrators of the Laffer Curve are nevertheless enjoying the success of their napkin doodle tremendously. Laffer, Rumsfeld and Cheney met again for lunch last year, 40 years later, at the same hotel to reminisce. They even made this video to flaunt what has so successfully given cover to the unabashed conservative drive all these years to dissociate ever lower taxes with ever higher debt.

Cheney holds up Laffer's re-drawing at reunion lunch

Please subscribe if you haven't, or post a comment below about this article, or

click here to go to our front page.

Obviously it depends on which side of the peak you are as to whether cutting taxes will be going uphill or down. But how do you find the peak’s location?

The Laffer theory is an asymptotic theory. You cannot determine peak’s location by considering only the short term. There is a time lag between tax policy changes and behaviour changes.

You can guarantee that, wherever you are on the Laffer curve, any tax hike will result in increased tax take immediately afterwards, because deals already in the works cannot be aborted easily.

But there is a more important question: should we be trying to maximise tax revenues at all?

Even if we suppose that the government itself is perfectly efficient in its use use of revenues [highly improbable], high taxes put considerable fiscal drag on the economy. Human nature is to seek to minimise tax liability. And the higher the taxes, the greater will be the effort “wasted” in fighting taxes.

Some very bright people make a good living out the fight to minimise taxes. A low tax regime would release a flood of talent to solving real problems rather than arbitrary tax problems.

Similarly, high tax distorts behaviour away from the economically optimal.

Throw in government waste, and it is not hard to understand why high taxes result in a net drag on the economy.

Suppose the drag is only 3%. Does not sound like much – after all that means the economy is at 97% of optimal! But when you compound 97% over 23 years you find the economy is smaller than half what it would have been. Eliminate that 3% drag, and in just one generation you have double the taxable economy.

Many of the negative effects of the tax system could be mitigated by a simple gross receipts tax instead of an intrusive, complex profits tax. But as long as the tax rates are high, the political demand for reliefs will be overwhelming, and the complexities will soon come back.

The waste issue is harder to tackle. And the bigger is the government, the more scope there is for corrupt special pleading and bureaucratic waste.

All of the above say that we should be thinking very hard about what absolutely must be done via the government, because there seems to be no other way.