Federal Court Throws Down Gauntlet Challenging NSA

The Supreme Court has several times deployed stratagems that insure that the government or corporations may continue unimpeded to do as they choose without interference from a pesky public. The Court has more than once ruled against class actions, leaving individuals to combat corporations on their own, and has ruled that plaintiffs do not have “standing” to sue the government. That is, they cannot sue on principle to right a wrong if not damaged themselves, and if they cannot prove they were affected because a secret government action prevents them from knowing of it, they have no right to challenge.

The explosive revelations by Edward Snowden of massive spying by the NSA should change that — which is not to say that anything will in fact change, given this Court’s posture. But the justices will need to come up with some convoluted logic to again rule — when one or more of several cases reach their chambers — that plaintiffs still have no standing. This time they will have to explain to us why the protection against “searches and seizures” of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution speaks of something that absolves the collection and retention of five years of some 300 million Americans’ phone call contacts.

The first case to obtain a ruling at the federal court level was decided in mid-December against the government and in favor of the several parties who brought the suit, principally Larry Klayman, a conservative activist and founder of Freedom Watch. Judge Richard Leon of the D.C. federal district court ruled that, now that we know that everyone’s phone records have been collected, Klayman’s et alia’s among them, the plaintiffs therefore this time have met the test of standing, and that the government’s actions run afoul of their Fourth Amendment rights. February’s catch-22

Just four months prior to Snowden’s bombshell, the Supreme Court used lack of standing to turn away a complaint brought by an alliance of human rights groups, journalists, lawyers and academics who argued that secret eavesdropping by the state on international phone and e-mail traffic could impair their work by compromising confidentiality, thus closing off contact with those outside the U.S. who know they are being spied upon.

The Court said the group could not prove they had been damaged or deprived of rights by the government’s surveillance: secrecy prevented them from acquiring the proof that they had been targeted by surveillance, so they lacked standing to sue. A kind of despair set in that the Court had decided to block any challenge to government spying. In the majority opinion, joined by Justices Roberts, Scalia, Thomas and Kennedy, Justice Alito wrote that because the plaintiffs “have no actual knowledge of the Government’s … targeting practices…the claims of the challengers that they were likely to be targets of surveillance were based too much on speculation and on a predicted chain of events that might never occur”. Alito asked us to consider that there may be little or possibly even no surveillance going on. And secrecy sees to it that a litigant has no ability to prove otherwise. Enter Snowden

The release of NSA documents in June showed that total surveillance was going on.

The Klayman ruling jumped ahead of similar suits, the most prominent being that brought by the American Civil Liberties Union right after Snowden’s revelations debuted. Like Judge Leon’s calling the NSA practices Orwellian, so did the ACLU invoke George Orwell’s seminal novel,”1984” as well as “The Lives of Others”, the oft-cited film about the Stasi, the security service that infamously was found to have kept files on every inhabitant of East Germany.

There are those who say they have done nothing wrong, are unneedful of the Fourth Amendment’s protection, and therefore have no problem with NSA’s collecting all their telephone activity. After all, it’s just data. NSA chief Gen. Keith Alexander stroked that complacency in a “60 Minutes” telecast in mid-December — the network was allowed unparalleled access to NSA’s innards evidently in return for not challenging any of its claims — saying, “There’s no reason that we would listen to the phone calls of Americans. There’s no intelligence value in that. There’s no reason that we’d want to read their e-mail. There is no intelligence value in that”.

By refuting a claim that no one is making, the intent seemed to have been to persuade that NSA’s activities are harmless. But phone call content is not ACLU’s argument. They say the greater violation of the Fourth Amendment lies in the ability to establish all the connections in our lives, which is how NSA does use phone metadata. In support of the suit, Edward Felten, a professor of computer science and public affairs at Princeton, made that case: “Calling patterns can reveal when we are awake and asleep; our religion, if a person regularly makes no calls on the Sabbath or makes a large number of calls on Christmas Day; our work habits and our social aptitude; the number of friends we have, and even our civil and political affiliations.”

“Calls to certain numbers — a government fraud hot line, say, or a sexual assault hot line — or a text message that automatically donates to Planned Parenthood” — can reveal some of the most intimate secrets of American citizens.

Judge Leon’s heavily researched and footnoted 68-page decision makes it clear that he is reaching well beyond Klayman’s allegation of hacked e-mail sent by the government in his name and the belief that “they are messing with me”. It is unimaginable that the Supreme Court would halt the entire NSA’s data collecting on the basis of claims that it might view as paranoid. The judge’s heavily researched and footnoted treatise brushes past that and — sure that this and other cases will move to the Supreme Court, — he is much more interested in the larger issue of the Fourth Amendment, finding that “plaintiffs have a substantial likelihood of showing that their privacy interests outweigh the Government’s interest in collecting and analyzing bulk telephony metadata and therefore the NSA’s bulk collection program is indeed an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment”. Leon uses information forced into the light since the Snowden releases. As we, too, have said earlier, given that “the government does not cite a single instance in which analysis of the NSA’s bulk metadata collection actually stopped an imminent attack, or otherwise aided the Government in achieving any objective that was time sensitive in nature”, he makes the case that the public’s expectation of privacy outweighs any claim this surveillance is essential to national security.

Because Congress, in authorizing the FISA court, has created a closed-end process that makes no provision for challenging that court’s secret rulings by the public or review by the nation’s courts, the judge wisely to confronts the question of whether his court — a federal court, no less — has the standing to challenge the data capture program on constitutional grounds. It’s a reasonable surmise that he is looking ahead to a Supreme Court that might be tempted to dismiss his decision by simply ruling that his court is permitted no jurisdiction. To head that off he cites a case (Webster v. Doe — 1988) in which decision “the Court stated emphatically that ‘where Congress intends to preclude judicial review of constitutional claims its intent to do so must be clear’”.

Both the ACLU and Judge Leon contest the precedent that the government uses to argue that phone surveillance is legal: 1979’s Smith v. Maryland. That Supreme Court ruling said that phone logs were not protected by the Fourth Amendment. But those were the logs of a single individual, and in a criminal case — “narrow surveillance directed at a specific criminal suspect over a very limited time period”, said the ACLU filing. In contrast, Judge Leon in Klayman fumes, “I cannot imagine a more ‘indiscriminate’ and ‘arbitrary invasion’ than this systematic and high-tech collection and retention of personal data on virtually every single citizen for purposes of querying and analyzing it without prior judicial approval”. He is sure that the Constitution’s author, James Madison, would be “aghast” at what he long ago so presciently forewarned would be “the abridgment of freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachments by those in power”.

Knowing that the government will appeal, Judge Leon stayed issuing an injunction that would demand NSA to stop its data collection.

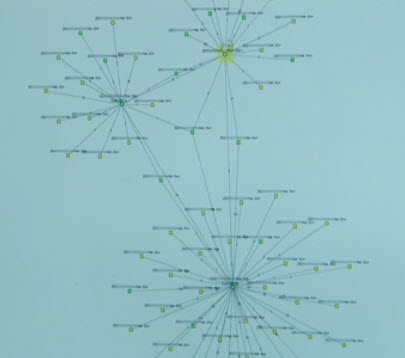

”Scraped” from the “60 Minutes” broadcast, the image shows NSA software linking the cross-connections between persons of interest and the numbers they in turn call.

And we recall Republican Congressman of Michigan Justin Amash asking by way of warning, “Have you talked to someone who has talked to someone who has talked to someone who might be a terrorist?” The spider web diagram above from the “60 Minutes” telecast shows how the metadata could find its way back to you .