Will the Supreme Court Finally Rid Us of Gerrymandering?

Apr 28 2018It is certainly strange in this putatively representative democracy that a corrosive practice just the opposite has been allowed since almost the nation's birth. Gerrymandering — the mapping of

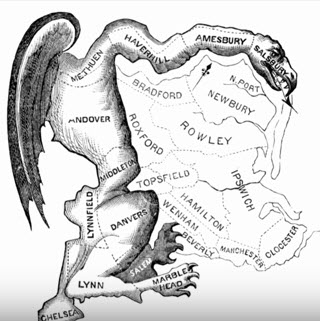

The original gerrymander, from the

Boston Gazette of 26 March 1812,

named after Governor Elbridge Gerry

for signing a bill that redistricted

Massachusetts to benefit his Democratic

party. It was thought to look

like a salamander.

electoral districts so as to all but guarantee outcomes — goes on and on. It dates from 1812.

In June or before, the Supreme Court is expected to have its say on whether a couple of states — Wisconsin and Maryland — have gone too far. The Court has several times in the past stepped in to halt mapping that is clearly race-based. It did so almost a year ago when it slammed North Carolina for packing blacks into two districts — "with almost surgical precision”, the court said — to remove their influence from neighboring areas. But the Court has never until now accepted cases where the gerrymandering has no racial component to justify the Court's involvement.

One reason for such diffidence is that the Constitution leaves it to the states to control "The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections", although it could be argued that gerrymandering doesn't quite fit those parameters. But that doesn't mean the states are free to violate principles elsewhere in the Constitution, and cases have been brought that say gerrymandering treats voters unequally, afoul of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

One solution is to turn over the design of election maps to non-partisan commissions. California led the way in 2017. Other states — Arizona, Florida, Iowa, Ohio — have taken measures with the same goal in mind, some planning for commissions for state legislatures, but not for Congress. But the great preponderance of states are free to go on subverting democracy with rigged mapping.

Pressure has mounted for the Supreme Court to stop avoiding the issue. As President Obama said in his 2016 State of the Union address, "we've got to end the practice of drawing out congressional districts so that politicians can pick their voters, and not the other way around". The Supreme Court justices sometimes seem unmindful of the problem. In a 2016 case of racial discrimination against North Carolina and Virginia, Justice Elena Kagan said about gerrymandering, "If it's politics, it's fine. If it's race, it's not".

For conservatives, the Democrats' "sudden enthusiasm for stopping gerrymanders reeks of hypocrisy and partisan optimism", said a National Review article of a year ago because Democrats benefited from the practice over many years in the past. The Wall Street Journal says the same: "Democrats didn't mind gerrymanders that helped keep them in power in the House for 40 years before 1994". But both fail to recognize how much more serious the engineering of electoral districts has become.

precision packingThe cause is sophisticated software's ability to maximize "packing and cracking" — stuffing a district with as many opposition voters as possible to cleanse surrounding districts of the objectionable, or ridding a district of opposition sectors so as to leave behind a majority of friendly voters — which has gone far beyond the hand-drawn redistricting of the past. In the Wisconsin case the plaintiffs took issue with the use of "pinpoint-precision technology that sliced-and-diced American communities". Moreover, political cartographers can today buy from Amazon and Facebook — as we have just seen — data that tell them details about people in given areas — what they buy, what they read, what they say. Coupled with voting records and census data on gender, race, and religion, mapmaking software can now engineer district boundaries with an exactitude that gives a client political party an invincible advantage. A paper published in the University of Chicago Law Review in 2015 has called what we have today "the most extreme gerrymanders in modern history".

Republicans in Wisconsin made no attempt to conceal their motives, naming their program "Redmap" and announcing its goal to "maintain a Republican stronghold in the US House of Representatives for the next decade". And Maryland? Observing what Democrats had done with the 6th district, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan said, "However much you think is too much, this case is too much".

But the justices have historically wanted no part of partisan dog fights. In one dissent, conservatives on the bench — Justices Alito, Roberts, and Kennedy — wrote that the right place to resolve partisan gerrymandering disputes was in the political arena.

Re: Wisconsin, Chief Justice Roberts showed an aversion to hearing such squabbles. He showed greater concern for possible damage to the Court than for the national weal, worrying about the "very serious harm to the status and integrity of the decisions of this court in the eyes of the country" were it to be dragged in to strike down one after another dispute favoring one political party or another.

The dilemma for the Court has always been the inability to settle on a standard by which to judge the fairness of voter apportionment to districts. Still, the country has come a long way. Before the Court settled on the principle of "one man, one vote" in 1964, states were unconstrained in their wildly uneven sizing of districts — Vermont, in one example, creating a district of only 36 people to guarantee a particular candidate's election to the state assembly, and California districts varying in size from 14,000 people to six million. Since then, the general practice has been at least to divide a state into equal districts reasonably equal in their number of people. Indeed, keeping them equal in population but stacked in favor of one party is what accounts for having to create such stringy shapes, earning for Pennsylvania's 7th district the sobriquet "Goofy Kicking Donald Duck". (The two cartoon figures connect where Goofy's paw boots Donald's rump, a connector that is no more than the width of the Brandywine Hospital).

Until disabled by the Roberts court in 2013, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 required nine mostly southern states to seek prior approval before instituting voting law changes. But that was to prevent racial bias. The question now is how to prevent the political imbalance that occurred after the 2010 census:

![]() In 17 states where Republicans drew the maps for this decade, their candidates won 53% of the vote but 72% of the seats.

In 17 states where Republicans drew the maps for this decade, their candidates won 53% of the vote but 72% of the seats.

![]() In the six states where Democrats were in control, their candidates took 56% of the vote but 71% of the seats.

In the six states where Democrats were in control, their candidates took 56% of the vote but 71% of the seats.

There are far greater disparities in a number of states.![]() In Pennsylvania, 13 of 18 House seats are owned by Republicans even though Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state.

In Pennsylvania, 13 of 18 House seats are owned by Republicans even though Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state. ![]() In North Carolina, Republicans hold 10 of the 13 congressional seats even though the purple state's voters are evenly split. The state representative who drew the maps said the state sent 10 Republicans to Congress only because "I do not believe it's possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats". Perhaps it was the same representative who, a year later, said, "I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country".

In North Carolina, Republicans hold 10 of the 13 congressional seats even though the purple state's voters are evenly split. The state representative who drew the maps said the state sent 10 Republicans to Congress only because "I do not believe it's possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats". Perhaps it was the same representative who, a year later, said, "I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country".

In cases before the high court in past years, the justices have acknowledged that gerrymandering is harmful, illegitimate, "manipulation of the electorate", etc. Justice Anthony has shown himself to be troubled by the distortions of gerrymandering and has indicated that he is open to judicial relief of partisan imbalance "if some limited and precise rationale" could be found to set district lines. No one has come up with "a workable standard" he wrote in a 2004 case.

In Gill v. Whitford, the Wisconsin case, his questions to lawyers defending Wisconsin's map were skeptical; he asked no questions of the lawyer representing the Democratic challengers. Kennedy also opened the door to applying the 1st Amendment — the 14th equal protection guarantee is the usual argument against gerrymandering — if it could be said that overly partisan redistricting suppresses free speech and amounts to punishing "citizens because of their participation in the electoral process, their voting history, their association with a political party." Justice Anthony Kennedy, as usual, is thought to be the swing vote.

solutions?One proposal dating from 1987 is called "partisan symmetry", a product of Harvard professors. It says, if district mapping causes one party to win 75% of the seats with only 55% of the votes, as an example, that's fine if in another election the opposing party fares the same, with 55% of the vote also yielding 75% of the seats. That idea seems wildly impractical. Mightn't the gerrymandering that produced the first outcome block the second outcome from ever happening?

Counsel arguing for Wisconsin Democrats proposed "efficiency" of a district's or an area's voting as the watchword. Devised by two University of Chicago professors, it works like this:

All votes for the losing candidate are counted as inefficient or "wasted". So are all votes for the winning candidate that exceed the 50% of the total vote that were needed to win. The difference between the wasted votes of the candidates is the "efficiency gap". Division of that gap by total votes cast yields a percentage and if that percentage exceeds a certain level — in Wisconsin, the plaintiffs proposed 7% — that suggests a district is lopsided and the map should be redrawn. (An example is found here).

The Democrats' attorney said that four of the five most out-of-bounds state legislature maps of the last 45 years were drawn since 2010. For the House of Representatives, it's eight of the ten most partisan, one of them being the subject of the Wisconsin suit.

Chief Justice Roberts again showed an obduracy to the Court's involvement saying, “It may be simply my educational background, but I can only describe it as sociological gobbledygook.”

This was too difficult for the editorial writers at the Journal as well, who called it a convoluted formula and said that both the Wisconsin and Maryland cases "argue strongly against judicial intervention". These are "equations giving the illusion of precision and, they hope, masking their underlying political motivation", masking that were either accepted they would be applied to both parties. Conservatives have lopsided control of the states, and the Journal writers are happy to keep it that way. When Democrats subsequently won a Wisconsin state senate seat that Republicans had held for 17 years, their editorial said that "refutes" Wisconsin's Supreme Court case. Gerrymanders can be overcome after all; all that is needed is a wildly polarizing figure like Donald Trump to come along.

If the Wisconsin hearing gave hope that some action might be taken, the Maryland session was deflating. Justice Stephen Breyer acknowledged that…

"It seems a pretty clear violation of the Constitution in some form to have deliberate, extreme gerrymandering. But is there a practical remedy that won't get judges involved in dozens and dozens and dozens of very important political decisions?

They gave off signals that once again the Court will waffle. Justices Ginsburg and Kennedy wondered is it too late to be dealing with this because there's not enough time before the November midterm elections; the justices don't like to decide things that are moot.

It looks like what Paul Smith, a lawyer for the Democratic voters in Gill, said to them in October fell on deaf ears:

“You are the only institution in the United States that can solve this problem just as democracy is about to get worse because of the way gerrymandering is getting so much worse”.

This is the last shot. The justices won't touch it again. So if they once again demur, saying partisan politics should be left to itself, failing to come up with some standard beyond which district rigging cannot go, they will have left this cancer to do its ravaging of democracy.

Please subscribe if you haven't, or post a comment below about this article, or

click here to go to our front page.

I like the idea of simply using available software to count heads, but can envision situations in which a resulting district might have a minority content of, say, 85%. This would assure minority representation by a candidate of choice, but it might also limit the number of such districts that might be represented by a minority candidate. If that percentage were lower, say 62%, the excess minority population might be shared with another contiguous district where the minority content might be increased to a point of viability. so, I would say, pay no attention to political data, but comply with the Voting Rights Act in reapportionment of political boundaries.