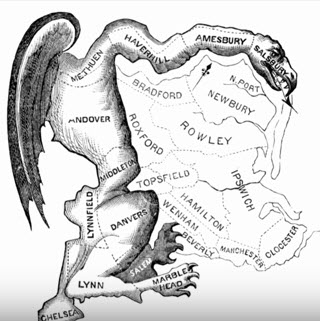

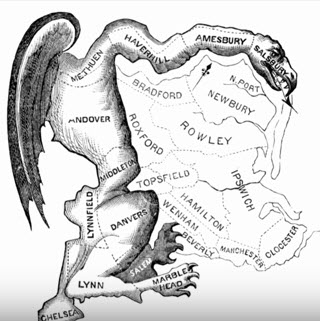

It is certainly strange in this putatively representative democracy that a corrosive practice just the opposite has been allowed since almost the nation’s birth. Gerrymandering — the mapping of

The original gerrymander, from the

Boston Gazette of 26 March 1812,

named after Governor Elbridge Gerry

for signing a bill that redistricted

Massachusetts to benefit his Democratic

party. It was thought to look

like a salamander.

electoral districts so as to all but guarantee outcomes — goes on and on. It dates from 1812.

In June or before, the Supreme Court is expected to have its say on whether a couple of states — Wisconsin and Maryland — have gone too far. The Court has several times in the past stepped in to halt mapping that is clearly race-based. It did so almost a year ago when it slammed North Carolina for packing blacks into

two districts — “with almost surgical precision”, the court said — to remove their influence from neighboring areas. But the Court has never until now accepted cases where the gerrymandering has no racial component to justify the Court’s involvement.

One reason for such diffidence is that the Constitution leaves it to the states to control “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections”, although it could be argued that gerrymandering doesn’t quite fit those parameters. But that doesn’t mean the states are free to violate principles elsewhere in the Constitution, and cases have been brought that say gerrymandering treats voters unequally, afoul of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

One solution is to turn over the design of election maps to non-partisan commissions. California led the way in 2017. Other states — Arizona, Florida, Iowa, Ohio — have taken measures with the same goal in mind, some planning for commissions for state legislatures, but not for Congress. But the great preponderance of states are free to go on subverting democracy with rigged mapping.

Pressure has mounted for the Supreme Court to stop avoiding the issue. As President Obama said in his 2016 State of the Union address, “we’ve got to end the practice of drawing out congressional districts so that politicians can pick their voters, and not the other way around”. The Supreme Court justices sometimes seem unmindful of the problem. In a 2016 case of racial discrimination against North Carolina and Virginia, Justice Elena Kagan said about gerrymandering, “If it’s politics, it’s fine. If it’s race, it’s not”.

For conservatives, the Democrats’ “sudden enthusiasm for stopping gerrymanders reeks of hypocrisy and partisan optimism”, said a National Review article of a year ago because Democrats benefited from the practice over many years in the past. The Wall Street Journal says the same: “Democrats didn’t mind gerrymanders that helped keep them in power in the House for 40 years before 1994”. But both fail to recognize how much more serious the engineering of electoral districts has become.

precision packing

The cause is sophisticated software’s ability to maximize “packing and cracking” — stuffing a district with as many opposition voters as possible to cleanse surrounding districts of the objectionable, or ridding a district of opposition sectors so as to leave behind a majority of friendly voters — which has gone far beyond the hand-drawn redistricting of the past. In the Wisconsin case the plaintiffs took issue with the use of “pinpoint-precision technology that sliced-and-diced American communities”. Moreover, political cartographers can today buy from Amazon and Facebook — as we have just seen — data that tell them details about people in given areas — what they buy, what they read, what they say. Coupled with voting records and census data on gender, race, and religion, mapmaking software can now engineer district boundaries with an exactitude that gives a client political party an invincible advantage. A paper published in the University of Chicago Law Review in 2015 has called what we have today “the most extreme gerrymanders in modern history”.

Republicans in Wisconsin made no attempt to conceal their motives, naming their program “Redmap” and announcing its goal to “maintain a Republican stronghold in the US House of Representatives for the next decade”. And Maryland? Observing what Democrats had done with the 6th district, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan said, “However much you think is too much, this case is too much”.

But the justices have historically wanted no part of partisan dog fights. In one dissent, conservatives on the bench — Justices Alito, Roberts, and Kennedy — wrote that the right place to resolve partisan gerrymandering disputes was in the political arena.

Re: Wisconsin, Chief Justice Roberts showed an aversion to hearing such squabbles. He showed greater concern for possible damage to the Court than for the national weal, worrying about the “very serious harm to the status and integrity of the decisions of this court in the eyes of the country” were it to be dragged in to strike down one after another dispute favoring one political party or another.

The dilemma for the Court has always been the inability to settle on a standard by which to judge the fairness of voter apportionment to districts. Still, the country has come a long way. Before the Court settled on the principle of “one man, one vote” in 1964, states were unconstrained in their wildly uneven sizing of districts — Vermont, in one example, creating a district of only 36 people to guarantee a particular candidate’s election to the state assembly, and California districts varying in size from 14,000 people to six million. Since then, the general practice has been at least to divide a state into equal districts reasonably equal in their number of people. Indeed, keeping them equal in population but stacked in favor of one party is what accounts for having to create such stringy shapes, earning for Pennsylvania’s 7th district the sobriquet “Goofy Kicking Donald Duck”. (The two cartoon figures connect where Goofy’s paw boots Donald’s rump, a connector that is no more than the width of the Brandywine Hospital).

Until disabled by the Roberts court in 2013, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 required nine mostly southern states to seek prior approval before instituting voting law changes. But that was to prevent racial bias. The question now is how to prevent the political imbalance that occurred after the 2010 census:

In 17 states where Republicans drew the maps for this decade, their candidates won 53% of the vote but 72% of the seats.

In 17 states where Republicans drew the maps for this decade, their candidates won 53% of the vote but 72% of the seats.

In the six states where Democrats were in control, their candidates took 56% of the vote but 71% of the seats.

In the six states where Democrats were in control, their candidates took 56% of the vote but 71% of the seats.

There are far greater disparities in a number of states.

In Pennsylvania, 13 of 18 House seats are owned by Republicans even though Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state.

In Pennsylvania, 13 of 18 House seats are owned by Republicans even though Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state.

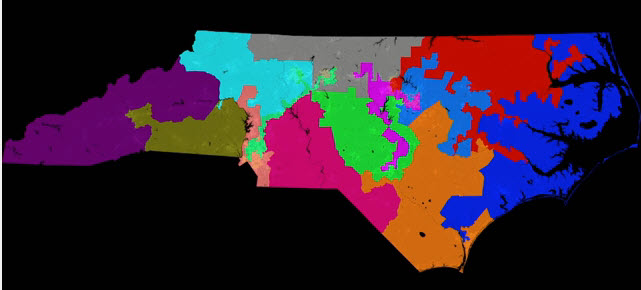

In North Carolina, Republicans hold 10 of the 13 congressional seats even though the purple state’s voters are evenly split. The state representative who drew the maps said the state sent 10 Republicans to Congress only because “I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats”. Perhaps it was the same representative who, a year later, said, “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country”.

In North Carolina, Republicans hold 10 of the 13 congressional seats even though the purple state’s voters are evenly split. The state representative who drew the maps said the state sent 10 Republicans to Congress only because “I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats”. Perhaps it was the same representative who, a year later, said, “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country”.

In cases before the high court in past years, the justices have acknowledged that gerrymandering is harmful, illegitimate, “manipulation of the electorate”, etc. Justice Anthony has shown himself to be troubled by the distortions of gerrymandering and has indicated that he is open to judicial relief of partisan imbalance “if some limited and precise rationale” could be found to set district lines. No one has come up with “a workable standard” he wrote in a 2004 case.

In Gill v. Whitford, the Wisconsin case, his questions to lawyers defending Wisconsin’s map were skeptical; he asked no questions of the lawyer representing the Democratic challengers. Kennedy also opened the door to applying the 1st Amendment — the 14th equal protection guarantee is the usual argument against gerrymandering — if it could be said that overly partisan redistricting suppresses free speech and amounts to punishing “citizens because of their participation in the electoral process, their voting history, their association with a political party.” Justice Anthony Kennedy, as usual, is thought to be the swing vote.

solutions?

One proposal dating from 1987 is called “partisan symmetry”, a product of Harvard professors. It says, if district mapping causes one party to win 75% of the seats with only 55% of the votes, as an example, that’s fine if in another election the opposing party fares the same, with 55% of the vote also yielding 75% of the seats. That idea seems wildly impractical. Mightn’t the gerrymandering that produced the first outcome block the second outcome from ever happening?

Counsel arguing for Wisconsin Democrats proposed “efficiency” of a district’s or an area’s voting as the watchword. Devised by two University of Chicago professors, it works like this:

All votes for the losing candidate are counted as inefficient or “wasted”. So are all votes for the winning candidate that exceed the 50% of the total vote that were needed to win. The difference between the wasted votes of the candidates is the “efficiency gap”. Division of that gap by total votes cast yields a percentage and if that percentage exceeds a certain level — in Wisconsin, the plaintiffs proposed 7% — that suggests a district is lopsided and the map should be redrawn. (An example is found here).

The Democrats’ attorney said that four of the five most out-of-bounds state legislature maps of the last 45 years were drawn since 2010. For the House of Representatives, it’s eight of the ten most partisan, one of them being the subject of the Wisconsin suit.

Chief Justice Roberts again showed an obduracy to the Court’s involvement saying, “It may be simply my educational background, but I can only describe it as sociological gobbledygook.”

This was too difficult for the editorial writers at the Journal as well, who called it a convoluted formula and said that both the Wisconsin and Maryland cases “argue strongly against judicial intervention”. These are “equations giving the illusion of precision and, they hope, masking their underlying political motivation”, masking that were either accepted they would be applied to both parties. Conservatives have lopsided control of the states, and the Journal writers are happy to keep it that way. When Democrats subsequently won a Wisconsin state senate seat that Republicans had held for 17 years, their editorial said that “refutes” Wisconsin’s Supreme Court case. Gerrymanders can be overcome after all; all that is needed is a wildly polarizing figure like Donald Trump to come along.

If the Wisconsin hearing gave hope that some action might be taken, the Maryland session was deflating. Justice Stephen Breyer acknowledged that…

“It seems a pretty clear violation of the Constitution in some form to have deliberate, extreme gerrymandering. But is there a practical remedy that won’t get judges involved in dozens and dozens and dozens of very important political decisions?

They gave off signals that once again the Court will waffle. Justices Ginsburg and Kennedy wondered is it too late to be dealing with this because there’s not enough time before the November midterm elections; the justices don’t like to decide things that are moot.

It looks like what Paul Smith, a lawyer for the Democratic voters in Gill, said to them in October fell on deaf ears:

“You are the only institution in the United States that can solve this problem just as democracy is about to get worse because of the way gerrymandering is getting so much worse”.

This is the last shot. The justices won’t touch it again. So if they once again demur, saying partisan politics should be left to itself, failing to come up with some standard beyond which district rigging cannot go, they will have left this cancer to do its ravaging of democracy.

Apr 28 2018 | Posted in

Law |

Read More »

Justices of the Supreme Court considering two cases (see companion article) wish there were some standard by which overly partisan gerrymandering could be struck down. Rather than petitioning the Court to hear one after another electoral district dispute, a standard would inhibit the states from drafting violations in the first place, knowing what would be the outcome.

What is dismaying is that the answer is hiding in plain sight, an answer that would do away with gerrymandering and partisan bias altogether, a solution that, inexcusably, none of the justices or lawyers for either party of these disputes seem to know anything about.

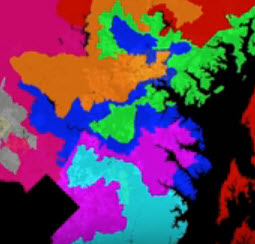

The answer lies in politically blind apportionment. Why couldn’t that same software, guilty of drawing grotesque monstrosities such as the Maryland district (pictured)

Blue marks the challenged

Democratic district, part of which

lies along Chesapeake Bay, in black.

before the court, be reworked to produce agnostic district maps across the country that pay no attention to political parties?

In fact, there’s already software that does precisely that. It’s now years ago that we — knowing software — claimed that the same population mapping software that creates gerrymandered abominations could be reconfigured to instead create districts that connect contiguous neighborhoods while, in the process, entirely ignoring the or racial contents or voting habits of the populations being assigned to each district. People would simply be counted — analyzed in no other way. We’d said,

Begin by dividing a state into the nearest to equal size rectangles that irregular borders and waterways permit. Iteratively expand or condense each area’s size and shape — with no regard to whatever political parties and ethnic groups predominate in the areas being manipulated — until each district’s population equals the others in the state, and each district is compacted to tightly represent one location or region.

It’s since been done. Appalled by the corruption of gerrymandering, a Massachusetts software engineer named Brian Olson pulled it off as we reported years ago. He created software — open source — that you could even run on your home computer, software that could apply the same uniform algorithms to the census maps of all 50 states. The wasteful and contentious lawsuits and court cases would vanish.

Since we first came upon him a few years back, he’s gone on to make this something of a crusade, replete with TED talk.

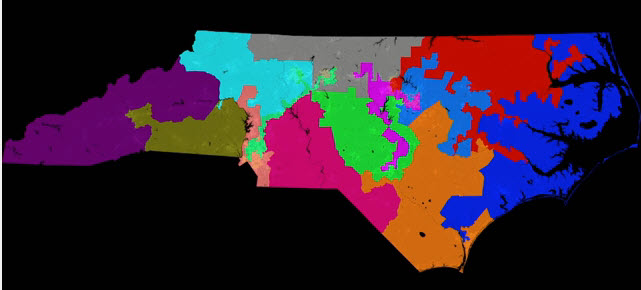

North Carolina provides an example. Republicans took over both the governorship and the legislature in 2010 and set about drawing Gerrymandered maps so aligned against blacks that the Supreme Court threw them out, causing the delay of the state’s primaries from March to June. Here is the original offending map of North Carolina, followed by Olson’s reworked, neutral rendering:

“The Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations”, says the same sentence in the Constitution that gives Congress control for setting the rules of elections. Congress could pass a law tomorrow to move to a system of proportional representation that would be rid of the whole disreputable practice of self-interested politicians drawing maps with the sole purpose of keeping themselves in office.

But for them, the country comes second. Self-interest blocks the path. And there is this side effect, which is so apparent: With re-election secured in districts Gerry-rigged in their favor, representatives have no need to compromise in their job of creating and passing new law.

Apr 28 2018 | Posted in

Law |

Read More »

<|200||>Dear Let’s Fix This Country:

I applaud your stated objective of fostering a non-partisan dialogue to make the US a better nation.

The view from a foreign country (we live in Canada) may not be of interest to you but I can state with knowledge and conviction that the US is viewed very negatively at this time from north of the 49th parallel — and speaking with friends and acquaintances from around the globe, that view is shared by many in countries that have been traditional allies of the US. This is not good for the US and it is also not good for the rest of the world — other than the primary opponents of the US.

The US did not end up here in one sudden leap, although the election of Trump was very negative step-change, but instead has been a progressive deterioration. In the time of Reagan, I admired the US — despite some of his administration’s flaws. One could point to the US and, despite some flaws, feel that the country was in general ethical and a positive influence on the world. I no longer feel that way and I am by no way unique.

There are many things wrong with the US at this point. However, in my opinion, they are all presently unfixable for one simple reason: campaign finance. Those with money can completely dominate communications and all other facets of the election process in complete disproportion to the influence they should have: the principle of one person, one vote has been completely subverted by your campaign finance rules.

There are also many things wrong with Canada in my view, but one thing we have correct (at the federal level) is campaign finance:

Only donations by individuals are allowed.

Only donations by individuals are allowed.

No donations by foreign entities.

No donations by foreign entities.

No donations by companies.

No donations by companies.

No donations by unions or other organizations.

No donations by unions or other organizations.

Any one individual is capped in terms of how much they are permitted to donate — currently just under CAD$1,600 per year to any one (registered) party.

Any one individual is capped in terms of how much they are permitted to donate — currently just under CAD$1,600 per year to any one (registered) party.

Third-party election advertising is restricted during the elections — this would be problematic to institute in the US as your ‘campaigns’ run for such massive periods, however no problem is insurmountable.

Third-party election advertising is restricted during the elections — this would be problematic to institute in the US as your ‘campaigns’ run for such massive periods, however no problem is insurmountable.

Strict accounting rules apply to which everyone who is

Strict accounting rules apply to which everyone who is

standing for election must adhere.

These regulations prevent anyone from buying undue influence with

politicians and also prevents anyone buying the communication channels that reach voters. Only those who represent the mainstream of society are in position to raise sufficient funds to run effective campaigns — the fringe elements / extremists do not gain a voice of significance as they

are unable to raise sufficient funds to unduly influence the outcome.

This of course will be difficult for the US to adopt due to your free speech mindset — and don’t get me wrong, free speech is fundamental cornerstone to any strong democracy. However, what you have on your hands today is a sick perversion of the intent of your founding fathers. The debate needed within your borders is a discussion asking: do you put limits on ‘free speech’ by limiting the money spent on partisan activities (during an election) or do you permit the free-for-all where those with money can totally dominate the message?

I suggest to you that your efforts would bear the greatest fruit in the

long term, if you take this topic on and are able to influence a change

related to campaign finance.

Sincerely,

J von Specht

Canada

Apr 24 2018 | Posted in

Zeitgeist |

Read More »

Virtually moments into his presidency, Donald Trump backed the United States out of the 12 nation trade deal, the Trans Pacific Partnership, or TPP, that had taken years to negotiate. For him it was a twofer: he could please his base, which thinks any trade deal threatens their jobs, and he could reject a major initiative of Barack Obama as part of his campaign to overturn everything accomplished by America’s first black president.

But now he wants to reconsider.

That has been a recurring pattern with this president. Mr. Trump entered office with firmly held opinions but only superficial knowledge of the subjects with which he would have to deal, yet he has repeatedly made impetuous decisions only to learn afterward that they were ill-informed and needed walking back. Defense Secretary James Mattis observes that a Trump decision can be like the weather: if you don’t like it, just wait, it may change.

Trump just did it once again when he told a crowd in Richfield, Ohio, that “We’re coming out of Syria, like, very soon”. Taken by surprise, his advisers scrambled to come up with how that meant we would not fully withdraw, of course, because that would create a vacuum allowing for the resurgence of ISIS and al Qaeda.

tariffs

Thinking he could take action without any reaction, he suddenly, and without consulting with advisers about likely ramifications, announced tariffs on two entire commodities, steel and aluminum. Only after his proclamation did he learn that he missed his principal target — China — and is hurting the wrong trading partners, Canada most prominently. He has since had to waive the tariffs for one after another country. China retaliated. They took aim directly at Trump’s voter base, cutting back imports of soybeans and pork. Farmers from Kansas through the Dakotas are distraught. ” If he doesn’t understand what he’s doing to the nation by doing what he’s doing, he’s going to be a one-term president, plain and simple”, said one North Dakota farmer.

climate

Last June, Trump announced that the U.S. was withdrawing from the Paris climate accords, calling it as usual a bad deal, making this country a pariah among all the nations on Earth — 195 countries had signed on — and not by accident undermining the global initiative in which Barack Obama was heavily invested. Hoping to head him off, 630 business leaders had signed an open letter to Trump; 25 companies including Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft had bought full-page ads in the major newspapers urging the U.S. to remain because the agreement will “generate jobs and economic growth” and “U.S. companies are well positioned to lead in these markets”.

That seemed to sink in only after the damage was done. Wanting a voice after all, Trump began to retrench, authorizing (we assume) the U.S. delegation that showed up at the U.N. climate talks in Germany last November, where a State Department undersecretary had this to say:

“Although he has indicated that the United States intends to withdraw at the earliest opportunity, we remain open to the possibility of rejoining at a later date under terms more favorable to the American people.”

Every deal made by others is a bad deal for Donald Trump. In business, his deals would have been with a couple of people across the table. Is that what makes him blind to the absurdity of stipulating new terms to 195 countries as if across the table there will be only a single person with “195 nations” penned on a conference name tag?

iran

It is the same with the Iran agreement. Trump has repeatedly called “one of the worst negotiated deals of any kind that I have ever seen”. The accord never contemplated going any further than being an arms control agreement limited to nuclear weapons. When Donald Trump called the deal “an embarrassment” in July, he had evidently lost sight of that limitation. Forgotten is how difficult it was to arrive at even that. The talks took a grudging 20 months, punctuated by disputes and walkouts and needing repeated deadline extensions as negotiators fought over final terms and language. Trump’s notions that there could have been a better deal are groundless; the Iranian negotiators were obdurate. The concern on our side of the table was that they would quit the talks.

In May, Trump is required once again to decide whether Iran is in compliance. With Tillerson and McMaster gone, who with difficulty managed the last time to get the president to hold off, Trump is expected this time to drop out of the Iran accord, paying no heed to our negotiating partners — Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia. That will do away with the one restraint already in place, doubling the Iranian problem by creating a second intractable nuclear aspirant to deal with.

pacific overtures

Which brings us back to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Having walked away from the deal literally on his first day in office, President Trump has woke up to what a blunder that was. With Trump quitting the field, into the void has stepped China, deliberately not one of the countries bordering the Pacific that are in the pact. The TPP was promoted by President Obama as a bulwark against China; without it he warned that we risk allowing China to set the rules.

There was at least a possibility to propose renegotiation at that point — to get rid of its more imperialistic ambitions. But Trump blew it by simply viewing it as his first on the revenge list against Obama. (He literally nixed the TPP on his first day in the White House). These pages four years ago railed against the TPP, not against Obama’s hopes to create a trading bulwark to ward off Chinese dominance in the region, but for the secrecy, for Obama’s wanting to push the agreement through Congress on a “fast-track”, no changes, no amendments, up-or-down vote.

In mid-April Trump directed advisers Larry Kudlow and Robert Lighthizer to see whether we could regain membership in the pact — after getting a better deal, of course. This time Trump is on to something, but likely doesn’t know what. Once again, he appears to think the U.S. can dictate revisions to an agreement that literally took years of negotiation (it was set in motion by Bush Jr. in 2008).

Here is what the president should focus on:

600 representatives of corporations were privy to the agreement’s contents for review. Some of the provisions were written by them, it was reported. To enforce provisions of the treaty, corporations would be able to sue governments directly, sidestepping a nation’s court system and its laws by bringing cases before special World Bank and United Nations tribunals, with the host nation bound by the compact to compensate the corporation in the event of adverse rulings.

600 representatives of corporations were privy to the agreement’s contents for review. Some of the provisions were written by them, it was reported. To enforce provisions of the treaty, corporations would be able to sue governments directly, sidestepping a nation’s court system and its laws by bringing cases before special World Bank and United Nations tribunals, with the host nation bound by the compact to compensate the corporation in the event of adverse rulings.

Companies can challenge a country when its laws conflict with the trade agreement. Under what are called “investor state” rights, they can even claim compensation for the alleged loss of “expected future profit”. Multinational companies will finally have found the grail: power greater than that of the sovereign states in which they do business.

Companies can challenge a country when its laws conflict with the trade agreement. Under what are called “investor state” rights, they can even claim compensation for the alleged loss of “expected future profit”. Multinational companies will finally have found the grail: power greater than that of the sovereign states in which they do business.

Foreign companies could sue for exemption from a country’s laws. They could complain that a nation’s food inspection laws exceed those of their home country, for example. Or that product safety regulations go beyond the trade pact and that import of their goods should not be blocked. One need only think of the range of problems the U.S. has had with Chinese imports — toys with

Foreign companies could sue for exemption from a country’s laws. They could complain that a nation’s food inspection laws exceed those of their home country, for example. Or that product safety regulations go beyond the trade pact and that import of their goods should not be blocked. One need only think of the range of problems the U.S. has had with Chinese imports — toys with

lead paint, toothpaste with diethylene glycol, wallboard that has made people ill.

Low wage foreign companies would be free to undermine our minimum wage laws. They would be exempt from any environmental regulations that exceed whatever is universally agreed to by the member countries — which is sure to set a very low bar. A foreign mining company could probably blow past regulations that ban our companies from mining in an area with risks to the water supply.

Low wage foreign companies would be free to undermine our minimum wage laws. They would be exempt from any environmental regulations that exceed whatever is universally agreed to by the member countries — which is sure to set a very low bar. A foreign mining company could probably blow past regulations that ban our companies from mining in an area with risks to the water supply.

All government contracts would be open for bidding by foreign companies. Job creation policies that require a contractor to use American labor and manufactures would be outlawed. We would see the American tax dollars that pay for such contracts go to foreign corporations.

All government contracts would be open for bidding by foreign companies. Job creation policies that require a contractor to use American labor and manufactures would be outlawed. We would see the American tax dollars that pay for such contracts go to foreign corporations.

The U.S. participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership was viewed as key by the other members, but they’ve gone on without us, signing the deal in Chile this March. Learning of Trump’s about face, but only if the U.S. is given a “substantially better” deal, says that Trump has no idea what is meant by a carefully wrought deal across 11 countries. His notion of special accommodations for the U.S. has so far met with a representative of one of the countries as “ridiculous”.

Apr 24 2018 | Posted in

World |

Read More »

The moment Donald Trump took office, the U.S. Navy pressed him to keep his word. While campaigning, the future president had pledged to expand the fleet to the 355 front-line warships the Navy and its supporters had been urging for years to meet the new threats posed by Russia and China. The cutback after the end of

The USS Hopper, Active in affirming freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.

the Cold War, when Reagan-era spending boasted a fleet of 594 ships, 15 of them carriers, had left the Navy with a mere 275 ships, a total inadequate to the demands placed on it to patrol the world’s seas.

The Navy had at the ready its “Force Structure Assessment” that called for building out the fleet with more carriers, submarines, destroyers and amphibious assault ships. They declared their plan “executable”. Their “2018 Navy Shipbuilding Plans” was already in the works. Implementation would be subject to Congressional budget allocations, of course, but a stronger military was Republican doctrine and the government — from White House to Capitol Hill — was now under Republican control.

True to plan, in mid-December, Congress passed and President Trump signed the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act which made a 355-ship Navy national policy, to be achieved “as soon as practicable”. To meet the global needs of combatant commanders the Navy assessment for 2018 called for 12 carriers, 104 large surface combatants, and 66 attack submarines.

Yankee go home

The Navy’s concerns are justified. Both Russia and China chafe at the United States setting the rules of a world order and the effrontery of our navy projecting its power wherever it chooses, from the Black and Baltic Seas bracketing Russia, to the seas wrapping China. President Vladimir Putin wants to restore some of the glory of the vast Soviet Union, the loss of which he has described as “the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the [20th] century”. China’s military doctrine has pivoted from “the traditional mentality that land outweighs sea”, replaced by “Great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans”.

China is bent on surpassing U.S. power, one aspect being to control their surrounding waters. The scope goes well beyond the shoals and rock formations in the South China Sea that have been built out with barracks and runways for fighter jets. China has a long-held and secretive plan that shows up on certain maps — a series of dash lines drawn ever-outward from their coastline, the first to embrace a number of island chains of disputed ownership claims, the second further into the Pacific encompassing as far as America’s Guam, the third far deeper into the Pacific to butt up against the Aleutians and Hawaii. Americans would do well to become aware of the ominous intention to drive the U.S. from the Pacific. We covered this is in our 2015 series “War With China: Is It Already Here?“, “China’s Master Plan: Drive Us Out of ‘Their’ Pacific“, and “China’s Military Build-up — It’s Aimed at Us“.

shrinking pains

In trying to do as much as before with too few ships, the Navy has invited a slew of problems. There had been three reports across two years by the Government Accountability Office warning of an over-extended Navy that, despite an 18% fleet reduction since 1998, had kept up its regimen of 100 ships always overseas. Carrier-based F/A-18 fighters were in the air 8,000 or 9,000 hours against their rated lifespan of 6,000 hours. Combat aircraft stayed on the ground or on deck for lack of spare parts. Too little time had

been dedicated to training crews. Sailors arrived at their ships with inadequate skills and were then worked an average of 108 hours a week instead of the Navy’s standard 80-hours. When in port, the Navy has traditionally put its sailors through months of 3-to-5 week courses to teach them the seafaring skills that have made it the world’s best navy, yet the GAO report said that ships based in Japan had “no dedicated training periods”. In September, the GAO told the House Armed Services Committee that more than a third of the ships in the Japan-based Seventh Fleet had expired warfare-training certifications.

Deployments had been stretched from the standard six months away from home per 18-month period to nine months or longer, wearing on both ships and sailors. Maintenance had been deferred or eliminated.

The deficiencies came to light after four incidents in a year, culminating with two collisions last June and August that left 17 sailors dead or missing.

The USS John S. McCain, with a hole after a collision, being escorted to Singapore

Afterward, the media reported these shortcomings, but without much mention of the ships’ command responsible for the ships and the crew’s lives. At any moment there’s the exec officer on the bridge if not the captain, radar operators, navigators, crew standing watch in harbor approaches, computers calculating other ships’ speed and direction. So how lax must have been the command discipline for these collisions to have happened? Lax enough, evidently, for the Navy to announce in January the court-martial of the officers who commanded the ships and charge them with negligent homicide, dereliction of duty, and hazarding their vessels.

resisting china

It is with this overworked Navy, these mishaps having raised questions about its readiness, that the U.S. is testing China’s claims that the South China Sea is its private lake. A U.S. destroyer, making one of many freedom of navigation statements, just sailed within 12 miles of one of the Spratly Islands on which China has built a base well offshore of its mainland. Twelve miles is the closest the laws of the sea allow a ship to come to the land of another sovereign nation without permission; the U.S. does not honor China’s claim that the Spratlys belong to them. China called the sail-by “a serious political and military provocation”. This was a repeat of a January sail-by of Scarborough Shoal, another of China’s build-outs, and one far closer to the Philippines than China. (Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, with whom President Trump says he has a “great relationship”, has turned his back on the U.S. and caved in to China, no longer protesting these island takeovers). In the January incident, China says our ship was chased off by one of its frigates. True or not, it says that a clash is inevitable if we elect not to allow China to re-write the rules of the open sea.

Chinese scholars point to our Monroe Doctrine in defense of their newly aggressive posture in the South China Sea. It is an inapt comparison. The U.S. was defending the continent from European moves to thwart South America’s quest for freedom from colonization, whereas China’s moves to block U.S. patrols are the opposite — to end freedom of passage by all navies and commercial shipping.

a naval build-up

With a production rate five times that of the U.S. and a projected 78 submarines by 2020, the Chinese have partly opted for the quantitative advantage of cheaper diesel-powered boats. But by 2008 China already had an estimated 30 advanced, partly-stealthy subs and has since sent down the ways their first “boomer” submarine armed with nuclear missiles having a range of 4,500 miles that can reach Alaska or Hawaii — or the continental United States, if launched from out in the Pacific.

But if a contest flares up over control of its near seas or Taiwan, the Chinese mainland makes possible a hybrid land-sea war. China’s coast guard is outfitted with military weaponry, it has unmarked coastal warships, and China can deploy cyber attacks from land. They have precise cruise missiles, sophisticated mines, the aforementioned subs, and the DF-21D shore-to-ship missile. It can be launched from a truck, fly almost 1,000 miles over the ocean, and home in on a ship moving at 30 knots — a chilling threat to a carrier with over 5,000 men and women and 60-70 aircraft — and we need add, taking years to replace at a cost of $10-or-so billion. The Pentagon cannot be sure the DF-21D truly works but in 2007 a DF-21D variant destroyed an obsolete weather satellite that was orbiting the planet. The Navy is betting on its iffy ability to detect, track and destroy an incoming DF-21D for which the best they could hope for is an estimated window of 12 minutes — and only if they were that full 1,000 miles away.

Russia reaching out

Russia’s navy may be smaller than the U.S. Navy but they plan to build 100 ships by 2020 with technology that will perforce exceed that of our older ships. Their plan will augment a growing nuclear submarine force that is already first rate, as are their surveillance systems, both from drones and space satellites. Russia has long-range cruise missiles that could menace our ships and Putin recently announced a nuclear torpedo that he claims will outsmart all American defenses. He may be bluffing, say some experts, but like China, it says that Russia has chosen wisely to emphasize anti-ship weapons.

As with China, Russia has stepped out aggressively. About 20 of those new ships are slated for the Black Sea; not for its beaches did Russia annex Crimea in 2014 with its ideally situated naval base at Sevastopol.

Sevastopol, Crimea

In January, a Russian military jet buzzed an EP-3 Orion surveillance plane in international airspace over the Black Sea, coming to within five feet said its crew, forcing the U.S. Navy plane to end its mission.

Russia has big plans for its leased naval base in Syria at Tartus on the Mediterranean, from which a Russian ship supported its Syrian ground operations last year. Its ships range the North Atlantic and Baltic, the increasingly navigable Arctic, and both the U.S. coasts, from which its ballistic missiles and torpedoes pose a looming threat.

And from both these adversaries there is the threat of further asymmetric weapons already coming into being. War planners on all sides envision how swarms of “bots” — small drones — could be launched to seek out ships and deliver chemical or biological agents to kill their crews. To the degree that artificial intelligence (AI) is involved — for each member of the swarm to avoid the others as in a murmuration of starlings, or to find their prey — other nations have an advantage. When China’s Xi Jinping or Putin goes to the private sector for assistance, they daren’t say no. Not so America. China, announcing its Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, intends to become the “premier global AI innovation center” by 2030. Its funding of AI research dwarfs what the U.S. budget allocates. Putin has proclaimed artificial intelligence as the future. “Whoever becomes leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world”, he said. Whereas in the U.S., where the Pentagon is seeking help from Silicon Valley, the Google subsidiary that developed the AI software that defeated a Go grandmaster refuses to work with the military.

is the 355-ship navy happening

The foregoing outlines the situation the U.S. Navy faces. The question is whether the 355-ship Navy, consecrated as official policy, has become only a fond aspiration unrelated to fact. In January The Wall Street Journal took a look at December’s defense authorization act and concluded that shipbuilding was only following its usual spending pattern. And now we have the $1.3 trillion spending bill, signed just before Congress took its Easter break, that actually tells us what money has been committed to plan. It provides for only a $2.3 billion increase in shipbuilding over 2017. It’s a roster of 14 ships: one carrier, two DDG-51 guided missile destroyers, two Virginia-class submarines, three littoral combat ships; one expeditionary sea base; one expeditionary fast transport; one amphibious ship; one fleet oiler; one towing, salvage, and rescue ship, and one oceanographic survey ship. Both the carrier and the amphibious ship are replacements of existing ships, not additions to the fleet. And as is apparent, only seven of the remaining 12 are new combat ships. This is not a pace that will reach 355 ships anytime soon, and it falls far short of the pace of Russia and China reported above.

Which raises the question of whether Defense Secretary James Mattis and the Trump administration have quietly concluded that the Navy’s chief role is for its worldwide presence, the projection of an image of power rather than actual power, in the realization that the Navy holds ever-weakening odds in the face of guided missiles that can cover a thousand miles and fast, autonomous torpedoes that can hunt in packs like wolves — all of which are far cheaper than ships. Will we see the aircraft carrier — that majestic emblem of our rule of the seas — go the way of the battleship?

Apr 7 2018 | Posted in

Defense |

Read More »

The austerity of the last decade — remember the 16-day government shutdown over the debt ceiling, spending of almost a trillion dollars “sequestered” over 10 years, expenses needing to be matched by savings elsewhere? — has suddenly been turned on its head, the doctrines of the political parties flipped in parallel. Republicans, who have long argued for a balanced budget, have become the big spenders while the Democrats they have always accused of profligacy are now the deficit hawks.

In December, Republicans passed tax cuts that will cost $1.5 trillion across 10 years without a single Democratic vote. Shortly thereafter Trump signed a bipartisan deal that will boost spending another $300 billion over just two

years. And now he has signed a 2,400-page omnibus spending bill that will cost $1.3 trillion more. Where will all this lead?

comeuppance

On several occasions Donald Trump boasted of balancing the budget. “We can balance the budget very quickly …I think over a five-year period”, he said to Sean Hannity of Fox News in January, 2016 and went on to tell The Washington Post that April that he would get rid of the national debt “over a period of eight years”. Once president, Trump put forth last July a 10-year budget for 2018 that ended in 2027 with a surplus of $16 billion. (The Congressional Budget Office — CBO — scored it differently, however, coming up with a deficit of $720 billion.)

Reality has proven to be different. In December the tax reform act was signed into law. In February, the president unveiled his proposed budget for fiscal 2019. It foresees a deficit of $984 billion next year, and that’s without the $300 billion signed after the budget was developed (Trump’s budget does overlap some of the defense spending increase). In a memorable understatement budget director Mick Mulvaney said the president had — for now — given up on his July plan to balance the budget. Instead of eliminating the $20.35 trillion nation debt, the Trump budget would add $7 trillion over 10 years, and that assumes growth of 3% every year.

The likelihood that the 9-year expansion will continue at that pace, uninterrupted by set back or recession for another 10 years, is close to nil. In contrast, the Federal Reserve estimates that the economy will grow by 2.5% this year and then subside to 1.8% for the long run. The president disagrees. He thinks 3% is the minimum. Last fall he said , “I don’t see why we don’t go to 4%, 5%, even 6%”. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is taken in by the notion that growth would pay the entire cost of the tax cuts. As recently as the end of January he claimed once again that that if growth could be sustained at 3% a year, the entire “revenue hole would be filled “. And not just filled. “This plan will cut down the deficits by a trillion dollars”, he had earlier said.

buying votes?

The Trump and Republican plan is supposedly about growth. Apart from lower taxes being what some say is the reason for the Republican Party’s existence, we are told that tax cuts are needed to spur greater expansion of an economy already in possible danger of overheating. It’s illogical to think that several hundred billion of extra money dumped into the economy will have no effect (although that’s what Republicans insist about the $787 billion of the Obama stimulus), but the benefits of the sales pitch do not necessarily match up with what actually happens.

The cut in the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% is meant to serve the double purpose of keeping companies from leaving the United States as well as encouraging them to to invest. The law provides instant write off against taxes of capital expenditures for a few years, which investment should cause productivity to increase, which will yield higher profits, which should flow through into employee paychecks. Skeptics remembered George W. Bush’s no-strings tax holiday of 2004 in which corporations spent the money repatriated from abroad on stock buybacks and dividends. The naysayers’ more jaundiced assumption has been that corporations will do the same.

Critics also take note that as part of the deal to reduce the rate to 21%, Congress had pledged to close loopholes that had reduced 35% to an actual rate of of only 18.1% of taxes on profits on average, but that was all but abandoned. Unseen therefore is that corporate taxes have been effectively cut far further — as low as 8% after loopholes still in place according to one estimate. And the multinationals have been given discounted tax rates — 15.5% for cash and 8% for less liquid assets — for returning to the U.S. the estimated $2.6 trillion of profits held overseas. America’s corporations find themselves flooded by a tsunami of cash.

Very quickly after the tax plan was signed into law, a long list of companies announced $1,000 bonuses to their employees. Others raised wages, a more appreciable and ongoing commitment. Congress and the president were justifiably pleased that their intentions were playing out, although it is too soon to know how durable will be this trend. And signs are that the skeptics have not been proven wrong. A Morgan Stanley survey, conducted by its analysts across all the industrial sectors they monitor, found that barely one in five corporations would pass even some of the tax savings on to workers, and that companies plan to spend 43% of their surplus on stock repurchase. Another poll said banks will distribute 75% of their tax windfall not to investment in their companies or employees but to shareholders. The Wall Street Journal reported that companies are buying back their stock “aggressively”. Whereas some 300 companies had announced benefits for 3 million employees by mid-February, $3 billion of that in bonuses and $5.6 billion overall, that amount is dwarfed by the money going into stock buybacks — $171 billion announced by that same date according to research firm Birinyi Associates.

In a buyback, a company spends its money to reduce the number of shares out there which boosts the value of the remaining stock outstanding: the unchanged value of the company is divided among fewer shares, increasing the value of each share. The money spent into the economy for those repurchased shares? Some 80% of all stock is owned by the top 10% of highest income earners, so this is spending that stays with the top tier of the wealthy, benefiting few in the middle class.

Not to be forgotten is how much of a company’s stock and options are owned by the CEO, upper management and board members, who are voting to use the money for their own gain, both to increase their stock’s value and pay themselves dividends on those same shares. Politicians in Congress will remind the public come the elections about the gift of lower taxes they have bestowed on us, not mentioning the price to be paid in the future, and will expect rich rewards from big business to help fund their re-election campaigns.

what about growth?

We’ve said that growth is the supposed objective of tax reform. But there’s the question of how the economy will find the room to grow even if corporations do decide to spend on new hiring. With only an eye-popping 4.1% unemployed, businesses will have to turn to those who some time back, as far back as the recession, dropped out of the labor force, perhaps found a way to get on disability, and haven’t looked for work since. In 2000, nearly 82% of Americans between the ages of 25 and 54 were in the work force. Today the figure is 79%, which doesn’t sound like much of a difference, but it comes to 3.7 million potential workers who sit idle while corporations can’t find people with the ability to fill increasingly technical jobs. Widen the age brackets and you can get to a whopping 20% of adults in prime working years neither working nor trying to find work.

Businesses may find themselves bidding for the already working, offering bigger paychecks, and — with more money percolating through the economy — pushing up consumer prices. This has not been in evidence so far. February added 313,000 jobs and the fact that unemployment stayed at 4.1% suggests that roughly that many have begun to look for work. And pay rose almost not at all — 0.1%. But one month is not the future and with so much money added to the economy worries of inflation have caused much of the recent turbulence in the stock market — the fear that, after a remarkably long stretch of minimal inflation, things are about to be different. Reading the tea leaves, the Federal Reserve is already considering tightening the interval between the interest rate hikes it plans for this years to slow the economy sooner.

Inflation brings about higher interest rates. Investors won’t part with money unless interest is high enough to cover the loss in the value of their money that inflation will inflict. The near-zero low interest rate of the past decade has enabled the government to borrow cheaply. The interest cost on the debt was $263 billion or 6.8% of the 2017 federal budget and has been fairly constant over the last nine years. But the much larger deficits set in motion by the tax cuts; the ballooning Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid outlays as the full complement of baby boomers move through their later years; and everything compounded by inflation, they are a problem for the government, which lives on borrowed money. Even without some expensive calamity such as war, the government will need to pay ever higher interest rates to attract buyers of its treasury bills and notes. The CBO expected interest costs to reach $818 billion in 2027 — almost triple 2017. And that forecast was from before the tax cuts and the spending increases were voted in. That’s more than the budget for defense.

The government paying whatever it must in interest and sucking so much money out of the economy will be a problem for the private sector. The cost of money will become too great for businesses to borrow, homebuyer hopefuls will not be able to afford mortgages. We will see the economy slow and very likely slide into recession.

summing up

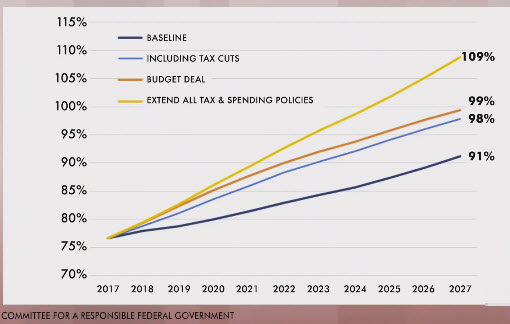

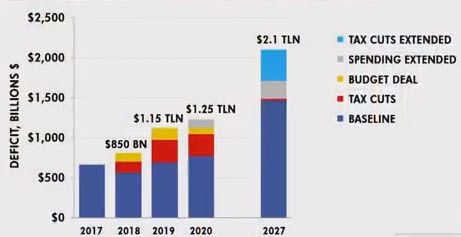

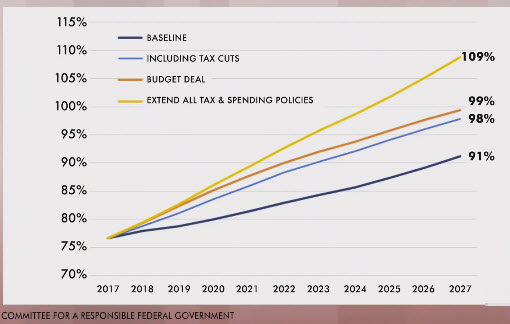

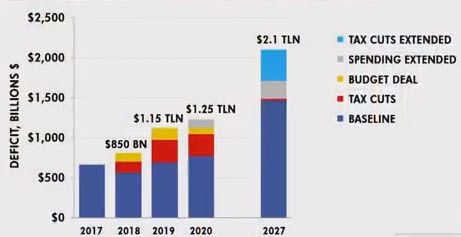

So, combining all elements — tax cuts, increased spending, portents of inflation, steep deficits, tripled interest on borrowed money — what does it all lead to? And, because it has just occurred, the following calculations do not include the just-signed $1.3 trillion spending bill!

The Trump administration inherited a deficit of $666 billion for 2017. Had nothing changed, that would have taken the national debt from 77% of GDP to 91% ten years down the road as seen in the baseline above. Then came the tax cuts, which elevated the projected debt in 2027 to 98% of GDP. The $300 billion extra spending took that to 99%. The tax cuts for corporations are permanent, but they are taken away from the citizenry eight years from now as prescribed by the tax law. That contrivance was a deceit necessary to hold its cost to $1.5 trillion and prevent the plan from coming out of the 10 years still running a deficit, a requirement for passing the law under “reconciliation” by a simple majority of votes, not one of them from Democrats.

But Congress will never let the tax cuts expire. They’ll be be extended, as will the defense spending boost which was authorized for only two years. Everything will be extended — that’s how Washington works — meaning that the cost of tax reform will zoom past $1.5 trillion. All is deception. Extending all will take the debt to 109% of GDP by the end of 10 years as seen in the top line of the graph.

How does that translate in dollars per year? The following chart is the mate of the one above and says that the 109% would derive from an annual deficit of a stunning $2.1 trillion in 2027. Let’s say that again: $2.1 trillion. Clearly, the country is reeling out of control.

Apr 3 2018 | Posted in

Economy |

Read More »

![]() In 17 states where Republicans drew the maps for this decade, their candidates won 53% of the vote but 72% of the seats.

In 17 states where Republicans drew the maps for this decade, their candidates won 53% of the vote but 72% of the seats.![]() In the six states where Democrats were in control, their candidates took 56% of the vote but 71% of the seats.

In the six states where Democrats were in control, their candidates took 56% of the vote but 71% of the seats. ![]() In Pennsylvania, 13 of 18 House seats are owned by Republicans even though Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state.

In Pennsylvania, 13 of 18 House seats are owned by Republicans even though Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state. ![]() In North Carolina, Republicans hold 10 of the 13 congressional seats even though the purple state’s voters are evenly split. The state representative who drew the maps said the state sent 10 Republicans to Congress only because “I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats”. Perhaps it was the same representative who, a year later, said, “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country”.

In North Carolina, Republicans hold 10 of the 13 congressional seats even though the purple state’s voters are evenly split. The state representative who drew the maps said the state sent 10 Republicans to Congress only because “I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats”. Perhaps it was the same representative who, a year later, said, “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what I think is better for the country”.